John le Carré’s Life Beyond The Pigeon Tunnel

There is scarcely a book of mine of that didn’t have The Pigeon Tunnel at some time or another as its working title. Its origin is easily explained. I was in my mid-teens when my father decided to take me on one of his gambling sprees to Monte Carlo. Close by the old casino stood a sporting club, and at its base lay a stretch of lawn and a shooting range looking out to the sea. Under the lawn ran small, parallel tunnels that emerged in a row at the sea’s edge. Into them were inserted live pigeons that had been hatched and trapped on the casino roof. Their job was to flutter their way along the pitch-dark tunnel until they emerged in the Mediterranean sky as targets for well-lunched sporting gentlemen who were standing or lying in wait with their shotguns. Pigeons who were missed or merely winged then did what pigeons do. They returned to the place of their birth on the casino roof, where the same traps awaited them.

Quite why this image has haunted me for so long is something the reader is perhaps better able to judge than I am.

—John le Carré, The Pigeon Tunnel

I felt sad when the novelist John le Carré died in December 2020, although I never met him personally, only in his novels. A few friends of mine, however, did know him, and whenever we spoke in recent years, I asked them for some details of his life—what was he like in person, how did he write his books, how did come up with his plots, etc.? That my friends knew and liked him drew me closer to his books and writing, and may explain my sadness when he died—that my friends had lost a friend.

At one point, after I read that le Carré had a connection to Switzerland (where I live), I searched some biographical entries and learned that he lived part of the year at a chalet in Wengen, a resort near Grindelwald and south of Interlaken. I was impressed that his address and phone number were in a local Swiss telephone directory, which suggest to me—as I sense in his novels—that despite literary fame le Carré always kept his modesty and common touch. I am sure he had gracious small talk for fans who recognized him in public.

Le Carré’s real name was David Cornwell. Early in my career I was at a meeting with a man who said he was David’s brother. Later I read a number of le Carré’s novels, and each time I would finish one I would wonder what parts of the stories were lifted from his early work as a British intelligence officer and what parts came from his imagination.

All that I knew then about le Carré’s professional life is that he had once worked for one of the British spy agencies (I didn’t know if it was foreign or domestic) and then had turned to novel writing in the 1950s. Later I read a biography of him, Conversations with John le Carré edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli and Judith S. Baughman, in which he says: “And I don’t know if I am a writer who turned spy or a spy who eventually turned writer.”

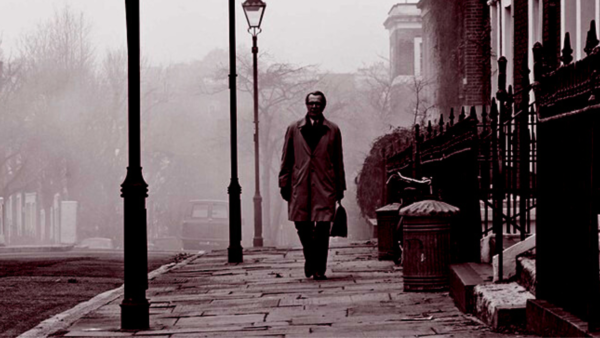

On one of my trips to London, in order to fill in some of the blanks about the underworlds that so interested John le Carré, I decided to take myself on a tour of London places mentioned in his novels. I had use of a London bicycle, and from the internet I printed out a file entitled “Explore Smiley’s London.” The subtitle read: “Explore some of the infamous London locations featured in John le Carré’s novels.”

As I flipped through the printed pages, I saw a large map of central London and a list with directions to such landmarks as “The Circus” (HQ of British Intelligence services located at Cambridge Circus), George Smiley’s home (9 Bywater Street in Chelsea), Battersea Bridge (“where Smiley grapples with an East German spy at the end of Call for the Dead”), and a few safe houses in London neighborhoods such as Camden.

It reminded me of the time when I first went to London as a student in 1974 and took a walking tour of Dickens’s London, although that was largely about mill buildings and coal bins. From my bike ride I hoped to come away with a better grasp of le Carré the writer or Cornwell the man. At the very least, when I next read one of his novels, it would be easier to imagine Smiley heading to the Circus, or Warsaw Pact operatives lurking near his house.

George Smiley didn’t seem to be at home when I biked to 9 Bywater Street in Chelsea to look at his elegant row house, now, I am sure, worth several million pounds. It was on this street that part of the television mini-series, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy—starring Alec Guinness as George Smiley—was filmed.

Le Carré was among the many who thought Sir Alec turned in a riveting performance in the film series, to the point that he later confessed on a lecture tour to a Seattle audience: “I had my character stolen by Alec Guinness. His voice and mannerisms entered my soul — to the extent that I didn’t know if I could finish the trilogy,”

Straddling my bicycle on Bywater Street, I wondered whether the current occupants get tired of Le Carré pilgrims rolling up their dead end street in central London. I stood across the street and furtively took a few pictures. Then I headed across town toward Cambridge Circus, which these days is less a nest of British spies and more ground zero of tourist London and the theatre district along Shaftesbury Avenue.

The Circus is at once a roundabout and the nickname for the headquarters of Smiley’s spy agency. Le Carré describes it this way:

From his window [Smiley] covered most of the approaches: eight or nine unequal roads and alleys which for no good reason had chosen Cambridge Circus as their meeting point. Between them, the buildings were gimcrack, cheaply fitted out with bits of empire: a Roman bank, a theatre like a vast desecrated mosque. Behind them, high-rise blocks advanced like an army of robots.

The building’s design, however, is faded colonial, one of those offices with an imposing façade where it’s easy to imagine cables running everywhere (the walls being too thick to bore through) and endless small conference rooms with scattered plastic cups of half-drunk coffee.

Across the street from Smiley’s office is the Palace Theatre and its many promotional billboards, and up and down Shaftesbury Avenue (always thronged with visitors) I could see theaters, bookstores, and busy cafés spilling into the street.

In Conversations, le Carré describes how the Circus evolved in his writing: “Not at the beginning: But then as I became more ambitious, I thought that it would in time work itself into a very beautiful microcosm of English behavior and English society altogether.”

I cannot say that there was much to see by the Thames and Battersea Bridge when I followed the map to see where Smiley “grappled” with an East German spy named Dieter. In the last sixty years I am sure there have been changes in riverboat moorings, and the houseboats described in the novel were no longer tied up along the bank. All I saw was normal barge and boat traffic on the river—not the swirling battle of two Cold War knights, locked in a death grip above dark waters (a bit like Holmes and Moriarity above Reichenbach Falls).

In Call For the Dead, le Carré describes the endgame:

Dieter’s hands were at Smiley’s throat, then suddenly they were clutching at his collar to save himself as sank slowly backwards. Smiley beat frantically at his arms, and then he was held no more and Dieter was falling, falling into the swirling fog beneath the bridge, and there was silence. No shout, no splash. He was gone; offered like a human sacrifice to the London fog and the foul black river lying beneath it.

I confess, I never thought of the bespectacled Smiley as someone capable of fighting off an East German asset, but I did get pleasure in stopping my bicycle along the Thames and thinking about le Carré, perhaps on his lunch break from MI5, working out the last scenes of his first Smiley novel.

After my day exploring Smiley’s London, I wanted to know more about le Carré’s personal life, I bought a copy of his memoir, The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from my Life, and reread his most autobiographical novel, A Perfect Spy, which contains a character resembling Cornwell’s father, Ronald Thomas Archibald “Ronnie” Cornwell.

Ronnie was a genial conman who, like a character from The Sting, spent his adult life running elaborate grifts and avoiding the law (not always successfully).

Leaving aside that David Cornwell published some of the most important novels of the Cold War, not to mention of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, in my view his great accomplishment is that he managed to live a fulfilled professional and private life despite having grown up on what sounds like “the run”. For example, in The Pigeon Tunnel, he writes:

My brother and I were the first in the family to be turned into fake gentry. We had to go to public school, willy nilly. For this my father always said that he was prepared to steal if necessary; and I am afraid he did. And so we arrived in educated middle-class society feeling almost like spies, knowing that we had no social hinterland, that we had a great deal to conceal and a lot pretending to do.

The mention of Cornwell’s brother prompted me to search online for the brother that I had met in London in the late 1970s. It turned out the Cornwell I had met wasn’t David’s brother at all—nor as best as I could work out even a distant cousin. Perhaps I had misheard the connection in our conversation, although I don’t think so. Perhaps family intrigue just followed le Carré?

David Cornwell was born in 1931 in Poole, Dorset, about fifteen miles east of T.E. Lawrence’s cottage at Clouds Hill and in the general vicinity of Thomas Hardy’s mansion outside Dorchester, although he did not grow up in literary company. His mother abandoned her family when David was five, and he became a ward of his Ponzi father and English public schools (whenever Ronnie could scratch together the tuition payments). In The Pigeon Tunnel, le Carré writes:

Today, I don’t remember feeling any affection in childhood except for my elder brother, who for a time was my only parent. I remember a constant tension in myself that even in great age has not relaxed. I remember little of being very young. I remember the dissembling as we grew up, and the need to cobble together an identity for myself, and how in order to do this I filched from the manners and lifestyle of my peers and betters, even to the extent of pretending I had a settled home life with real parents and ponies. Listening to myself today, watching myself when I have to, I can still detect traces of the lost originals, chief among them obviously my father.

Although I am sure he was insufferable to his children, Ronnie makes for wonderful reading, not just in The Pigeon Tunnel but when his alter ego speaks from the pages of A Perfect Spy, a confessional novel about a double agent trying to make sense of his confused identities when he was growing up.

In The Pigeon Tunnel, Ronnie is a charming rogue, forever borrowing a friend’s Rolls Royce to drop off his children at school (so the headmaster will think he’s good for the tuition checks, which he’s not). Le Carré writes:

Tension? Ronnie’s entire life was spent walking on the thinnest, slipperiest layer of ice you can imagine. He saw no paradox between being on the Wanted list for fraud and sporting a grey topper in the Owners’ enclosure at Ascot. A reception at Claridge’s to celebrate his second marriage was interrupted while he persuaded two Scotland Yard detectives to put off arresting him until the party was over — and meanwhile, come in and join the fun, which they duly did. But I don’t think Ronnie could have lived any other way. I don’t think he wanted to. He was a crisis addict, a performance addict, a shameless pulpit orator and a scene-grabber. He was a delusional enchanter and a persuader who saw himself as God’s golden boy, and he wrecked a lot of people’s lives.

By the time Ronnie makes it into A Perfect Spy, he’s the equally engaging Ricky Pym, while his son Magnus is working for both the Circus and the Czechs, as if to perpetuate the confusions of his own childhood on the lam. There’s a long passage involving one of Ricky’s wingmen, Syd, who tries to explain the father to the son. The conversation comes after his father’s death when Magnus is curious if there was a horse-drawn coach (as he’s been told) at his parents wedding:

“So was there really a coach then or was it all flannel?” I ask Syd.

Syd is always cautious in how he replies. “Now there could have been a coach, Titch [Magnus]. I’m not saying there wasn’t, I’d be a liar if I did. I’m just saying I never heard about a coach till your dad happened to mention it in church that morning. Put it that way.”

“So what had he done with the money—if there was no coach?”

Syd really doesn’t know. So many thousands of pounds have floated under the bridge since then. So many great visions come and gone. Maybe Rick gave it away, Syd says awkwardly. Your dad couldn’t say no to anyone, specially the Lovelies. Never right with himself unless he was giving. Maybe a con came and took it off him, your dad always loved a con. Then to my amazement Syd blushes. And I hear faintly but clearly from the side of his mouth the ratta-tat-tat he used to make for me when I was a child and wanted him to do the clip of horses’ hoofs.

“You mean he used the Appeal money to lay bets?” I ask.

“Titch, I’m only saying that that coach of his could have been horse-drawn. That’s all I’m saying… ”

In Conversations, le Carré says of Magnus: “He is the archetype of the double agent in all of us. We live much of our lives beneath the surface—like icebergs. Most of our thoughts and desires are unexpressed.”

How Cornwell escaped the flimflam world is anyone’s guess, but while still in his teens in the late 1940s he removed himself to Bern, Switzerland, and there took a respite from Ronnie’s confidence games and studied German.

David lived with a Swiss family, had a little romance, and found some stability in his life. One profile of him says: “He juggled his studies with working as a waiter in a train-station buffet, skiing… and [he] claims to have washed elephants for Switzerland’s Circus Knie….Home was a little room that always smelled of chocolate for it was next to the Tobler factory, where Toblerone was made. His interest in German literature came to the forefront time and time again outside of the university.”

Afterwards he did his British national service in eastern Austria, debriefing refugees who were struggling over or under the Berlin Wall. He got his university degree from Oxford in modern languages, although during his studies his father was declared bankrupt and David had to take some time off.

After Oxford, David taught languages at Eton, the elite public school. As it happens, a good friend of mine, the London publisher and literary agent Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, was a student in one of Cornwell’s German classes. He tells the amusing story of the time when Cornwell took a class to the production of a German play at a theatre in London. During intermission—it was a hot day—Cornwell bought the boys (who were all about age seventeen) gin-and-tonics from the theatre bar, which no doubt helped to boost his teacher evaluation.

From Eton, perhaps looking for more excitement in his life, Cornwell joined MI5. His spy career—later he moved over to MI6—lasted from 1958 to 1964, and in that time he was stationed in Bonn, ran agents, and began working on the novels that would become bestsellers, allowing him to write full-time. His third book, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, was published in 1963 and its success allowed him to leave spying—although in Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, one of the characters remarks: “I never heard of anyone yet who left the Circus without some unfinished business.”

Of writing, le Carré once said that a good novel had to have “empathy, fear, and conflict,” and he also said: “I never impose much the plot,” which may explain why in some of his weaker novels it can be easy to lose the thread.

In Conversations le Carré says: “The writer like the spy is an illusionist. He creates images that he finds within himself; he illustrates his universe with words from this immense world.” He adds: “If I had gone to sea instead of going to the spies, I would have written about the sea. Joseph Conrad did that, and used the seafaring life superbly as his theatre of man’s striving, with its own laws and language and morality, its own cruelties and rewards and glimpses of the infinite.”

John le Carré’s enduring character is George Smiley, the gentlemanly counter-intelligence agent who is forever chasing moles in the Circus (he finds one in his wife’s bed) and Karla, a KGB force of darkness on the far side of the Berlin Wall. (He eventually gets his man, although the hunt is more fun than the arrest—during which Karla drops his wife’s cigarette lighter in front of Smiley, to make the point that he, too, has penetrated Smiley’s soul.) In Conversations le Carré says of Smiley: “Professionally, he’s illusionless, and yet in love he’s the victim of self-deception.”

In reading Conversations, I was interested to see that le Carré made a connection in his mind between the good-cop Smiley (forever trying to right the injustices of the Cold War) and Ronnie, who was always one step ahead (or behind) the law. Le Carré says: “I probably took refuge in the world of espionage to escape my father. By inventing George Smiley I tried to conjure up the specter of my father…. My father’s moral concerns were nonexistent, and I heaped all of mine into Smiley. I think I made a bit of a new father out of him.”

In The Pigeon Tunnel his father is most on display toward the end of the book, when le Carré writes about his early years:

Adulthood was a dangerous place. From an early age I felt I was living on occupied territory. Because of the life we lived, I have mistrusted anything that looked respectable. I believed it was a sham. I saw Ronnie in majestic clothes, speaking well, with the regional accent somehow laundered out of him, and lying through his teeth. Still now my hackles go up secretly when meeting leading politicians. I’ve never believed that what I saw was true. You come into the house and I’m thinking, is he really from The Times? It’s always that tiny paranoid blip as I open the door: “what should I be thinking?” A little like Smiley.

The other figure hovering over the fiction of John le Carré is Kim Philby, the MI6 defector to Russia in 1963 whose betrayals, even now, cut across many currents of English political and social life. That an upperclass Englishman could end up shilling for the Soviets calls into question numerous articles of faith, and in many le Carré novels, without naming him, the search for the truth behind Philby’s deceptions is ongoing. It’s the specter behind Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, and in Conversations le Carré points out: “To this day no one realizes what havoc he created by delivering up dozens of our agents to a gruesome fate in the Soviet Union.”

While employed in the intelligence services, Cornwell was assigned to work on Philby’s “file”, and one way to look at le Carré’s writing is as a long internal investigation into who or what turned Philby against England.

Le Carré writes about his defection in The Spy Who Came in From the Cold: “In its way, it marked a boundary between two eras: the era of God-is-on-our side patriotism, of trusting government and in the morality of the West, and the era of paranoia, of conspiracy theory and suspicion of government, of moral drift.”

I was always interested in my friends’ talk about how Cornwell researched his novels. It seems he liked to travel—to the Middle East, Far East, Washington, DC, etc.—and when he got there he would often seek out the company of foreign correspondents and listen to their stories at press club bars. “I like to find a local contact,” he said in one interview. In The Pigeon Tunnel he describes this process when writing about a visit he made to the chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Yasser Arafat:

My journey to Arafat had been frustrating, but he was at that time a man so luridly portrayed as the elusive, wily, terrorist-turned-statesman that anything more comfortable would have been a disappointment. My first stop was the late Patrick Seale, the Belfast-born, Oxford-educated British journalist, Arabist and alleged British spy who had succeeded Kim Philby as the Observer newspaper’s correspondent in Beirut. My second stop, on Seale’s advice, was a Palestinian military commander loyal to Arafat named Salah Tamari, whom I first met on one of his regular visits to Britain. In Odin’s restaurant in Devonshire Street, while Palestinian waiters gazed on him in breathless awe, Salah confirmed to me what I had been told by everyone I consulted: if you want to go deep among the Palestinians, you have to have the Chairman’s blessing.

Le Carré’s novel about the Middle East is The Little Drummer Girl, and to write it he traveled to Syria, Jordan, Beirut, Tunis, and many times to Israel, where he told a local newspaper: “I knew nothing of the Middle East, but then I have always seen my novels as opportunities for self-education.”

My friend Jim Hougan, who has written books about the CIA and Watergate, had a number of dinners in Washington with Cornwell, who was always hunting for plot lines for his novels. I asked Jim whether le Carré had ever been to Russia and, while there, whether he had ever met Kim Philby, who lived until 1988. Jim wasn’t sure, but in Conversations I found the answers. Le Carré tells one of his interviewers:

And no, I didn’t know Philby. When I went to Moscow for the first time, in 1987, I met a man called Gendrik Borovik who said, “There’s a very good friend of mine, excellent patriot from your country who would like to meet with you. His name is Kim Philby.” I said, “Gendrik, you can’t possibly do that to me. I am going to the ambassador’s for dinner tomorrow night. I can’t be the guest of the Queen’s ambassador one night, and the Queen’s biggest traitor the next. It won’t do.”

In The Pigeon Tunnel, he tells a slightly longer version of the same story, writing:

In 1987, two years before the Berlin Wall came down, I was visiting Moscow. At a reception given by the Union of Soviet Writers, a part-time journalist with KGB connections named Genrikh Borovik invited me to his house to meet an old friend and admirer of my work. His name, when I enquired, was Kim Philby. I now have it on pretty good authority that Philby knew he was dying and was hoping I would collaborate with him on his second volume of memoirs, the very book that [Nicholas] Elliott [Philby’s friend and colleague] was convinced he had up his sleeve. In the event, I declined to meet him. Elliott was pleased with me. At least I think he was. But perhaps he had secretly hoped, all the same, that I might bring him news of his old pal.

I understand le Carré’s reluctance to meet Philby. I might have felt the same way. Still, I am sure both the novelist and the spy in le Carré would have savored an evening with the greatest British traitor of his generation, especially as, in general, le Carré did not much care for ambassadorial dinners or the British aristocracy (that world his own father was never able to penetrate, even during the best of his scams, such as when he stood for Parliament as a way of dodging his creditors).

In Conversations, while ruminating about his father and Philby, le Carré admits: “He [Philby’s own father] was tremendously dominating. I too had no mother though these years. I felt, thinking about Philby and his father, and myself and my father, that there could have been a time when I, if properly spoken to by the right wise man or woman, could have been seduced into some kind of underground act of revenge against society.” These feelings might explain his remark in another interview: “Philby was my secret sharer whom I never met.”

Instead le Carré’s double life became that of a novelist working for MI5 and MI6, and later on—who knows?—maybe he was doing a little intelligence work on the side while cranking out his best-selling novels. After all, he did meet the likes of Arafat in his travels, and he said of spying: “It’s a journalistic job done in secret,” which describes a lot about how he worked. He wrote his books in longhand, which his wife, Valérie Jane Eustace—an important collaborator—then typed and edited. He worked best in the mornings, and puttered in the afternoon. Over Scotch in the evenings, he would look over his day’s work. He liked to say of his plots: “I try to have a vision what the audience will remember leaving theater.”

Certainly le Carré was a product of his early, troubled years, as he confesses:

You will not be surprised to read then that in low moments, like many sons of many fathers, I ask myself which bits of me still belong to Ronnie, and how much of me is mine. Is there really a big difference, I wonder, between the man who sits at his desk and dreams up scams on the blank page (me), and the man who puts on a clean shirt every morning and, with nothing in his pocket but imagination, sallies forth to con his victim (Ronnie)?

He sounds like a man wanting to come in from the cold, or as he said in one interview: “I often feel like an actor looking for a part.”

About Matthew Stevenson

Matthew Stevenson, a contributing editor of Harper’s Magazine, is the author of many books, including Reading the Rails, Appalachia Spring, and The Revolution as a Dinner Party, about China throughout its turbulent twentieth century. His most recent book, about traveling in France and the Franco-Prussian wars, is entitled Biking with Bismarck.