Conversations: Bitan Chakraborty and Kiriti Sengupta

“Every detail is credible, anchored in the mundane reality of city-dwellers in urban metropolises in contemporary India. [Bitan] Chakraborty is not a fantasist or fabulist; reality is an unvarying constant in his stories,” writes academic and critic Indrajit Bose in the World Literature Today.

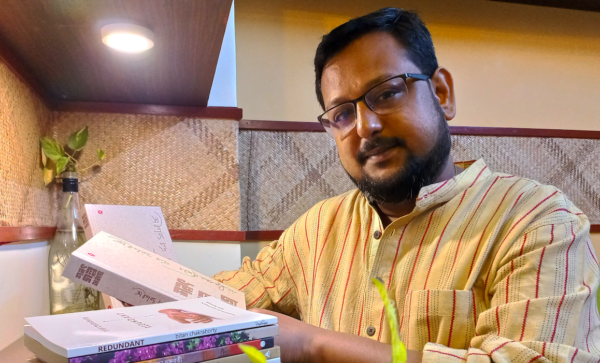

Bitan Chakraborty (b. 1984) spent twelve long years learning and actively participating in theater. Author of a few critically acclaimed books of Bengali fiction, Bitan is the founder-director of Hawakal, India’s leading independent press with two functional ateliers in New Delhi and Calcutta. Hawakal, a bilingual publishing press, promotes new talents and hosts established poets and writers like K. Satchidanandan, Sudeep Sen, Sanjeev Sethi, K. Siva Reddy, Shyamal Kanti Das, Bibhas Roy Chowdhury, Syed Kawsar Jamal, Sanjukta Dasgupta, GJV Prasad, Somdatta Mandal, Sreemati Mukherjee, Brinda Bose, and others.

I have published Bitan Chakraborty several times under the aegis of Shambhabi Imprint, working with him on his Bengali books and on two volumes of his short fiction translated into English. I also rendered one of his short stories in English, “Disappearance,” published in the EKL Review (December 2021). His first novella, Redundant, was released by Readomania (New Delhi) in May 2022. Bitan’s prose is highly accessible but culturally nuanced. So, reading his stories isn’t only about perusing the lines, but about leading his audience to a new world of learning.

—Kiriti Sengupta, 2022

Editor’s Note: I want to extend my special gratitude to Kiriti Sengupta not only for arranging this wonderful conversation, but for translating into English it as well. —DEP

Kiriti Sengupta: Among your peers (post-90s), you are probably the only Bengali writer who enjoys three notable titles in translation. Your latest, Redundant, has been in the news lately for creating ripples in contemporary Bengali fiction. Three different translators for these three books. Selecting the right translator must have been exacting for you.

Bitan Chakraborty: Unfortunately, not much Bengali short fiction has been translated in my time. It should have been the other way round. Maybe a dearth of translators, or perhaps, the authors have not been attentive enough to the exposure that translation allows. It’s true that I’ve been lucky; I have three full-length volumes rendered in the English language, and they are available across the world.

For any author, I must say, the primary challenge lies in finding the right translator—someone who can mirror the soul of your writing. Writers nurture specific political understanding in their works. So, the translators should ideally be able to reach it. It’s not about translating verbatim. There is profound inhibition at the core of good writing. I call it inhibition, but you may refer to it as introversion that refuses to get revealed. An efficient translator works on that reticence and unveils it before the readers. Therefore, translation in itself is an invention. Moreover, the aesthetics of the target language should always be kept in mind. Else, the translation becomes patchy. So, as I looked out for a translator, I cautiously exercised my observations. And I’m happy that I’ve been pretty successful at that.

KS: Dipankar Mukherjee (Publisher; Readomania) was elated when he first read the manuscript of Redundant. Then he proposed an epilogue to cater to the target readers. It took a while to convince you. Could you please tell me if you were concerned about the authenticity of the translated work?

BC: I initially disagreed with Dipankar when he proposed to add an epilogue to Redundant. From conceptualizing the original Bengali Haat Kata to finishing the novella, it took me slightly more than three years, and I was pretty convinced about the conclusion. As we launched the Bengali edition in 2019, many readers read it, but no one pointed at the ending. Also, my translator (Malati Mukherjee) didn’t find the concluding chapter objectionable as she translated the book. So, it was shocking when Dipankar advised me to work on an epilogue. We had a long discussion, and finally, I decided to give it a chance. It was like, how about exploring a new ending? It took me two months, you know! Meanwhile, I released another novella and a new short story collection. So, I was in a different mindset, and it was hard to return to my mood of the Haat Kata days. My next hitch was to keep the subtlety of the conclusion unruffled. Now, the readers will assess whether I have done it well.

KS: You are a publisher and a writer, or a writer and a publisher—equally consummate in both roles. Although you have been publishing fiction and non-fiction for the past 13 years in India, Hawakal Publishers Private Limited is the leading poetry press, especially in English-speaking and Bengali communities. However, on the other hand, you have authored three volumes of short fiction, two novellas, one book of prose, and translated two chapbooks. So, what’s happening in Bengali literature, especially fiction writing?

BC: Right, I’m blessed to be a writer and a publisher. I call it a blessing because had I not been a publisher, I would have never witnessed the publishing industry’s politics. Policies are made to accrue power, to achieve supremacy or superiority. So, as a publisher, I secure the rights of my authors, and as a writer, I can perceive what I should write and what I should not. There is a definite distinction between mainstream and alternative writing in Bengali literature. To earn quick popularity, writers often lead their readers to a world of unreal fantasy. On the other hand, most of the so-called parallel writers would pen theoretical discourses in the name of fiction writing. So, readers flee and can’t help but take refuge in the make-believe.

Some authors want to entertain their readers so they can temporarily forget their daily oppression, trauma, and sorrow. A group of writers offers thrillers to cater to the readers who fail to protest against the injustice they are subjected to. They believe stories should fulfill one’s wishes or aspirations. But unfortunately, nobody considers what’s next! Who would educate us on the difference between literature and television soap? Allen Ginsberg got numerous followers reading his poetry. Tagore’s worldwide reader base was based on his philosophical finesse. Did they commit to establishing a world of illusions? We must not forget Maxim Gorky.

Capitalist society thrives on illusory fantasies that curb our aptitude to fight against wrong. In a country like India, where a significant population struggles for a square meal and a proper education seems to be a far-fetched dream for ordinary people, should we not write about the real deals? A few authors write about these issues, but most stories remain boxed.

KS: You are currently curating a complete anthology of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay‘s Bengali short stories. Your introductory note is titled: “The Ease of Accessibility.” Do you think “convenience” is the quality that keeps literature afloat across the times?

BC: You know, we support complexity that feeds oppression, and finally, we are entrapped. Tyranny kills simplicity. Bob Dylan wrote: “How many roads must a man walk down / Before you call him a man?” His clarity is unmistakable. Similarly, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s short fiction is lucid and appeals to Bengali readers even now. The heart wells up with gentle compassion. This is the tender-hearted scholarship that leads one to liberation.

KS: Areeb Ahmad, in his critical essay, “Authors of The Other: Social Realism in Indian Fiction,” writes, “When it comes to social realist fiction, there is a fine line between giving voice to the voiceless and speaking on their behalf. The former makes space for them and the lives they have led; the latter attempts to box them into ready-made narratives where they are just soulless props for the writers to pat themselves on the back and feel good.” I believe Redundant marked the anterior space wherein you lent voice to Shubho and paved the way for him to take a drastic step, and thereby you transformed your work into speculative fiction. Was it a deliberate move from being a realist to being suppositional?

BC: Envisioning the climax is important to me. It is the ending that determines the itinerary of the characters. I accompany them as they travel the storyline. The journey is fascinating as well as frustrating—I get into the texture—I understand their love, joy, tension, disappointments, and failures. This is the truth of my stories. If I only depicted personal convictions, it would become an essay or a discourse. Readers may not be able to relate to my situation. My presence isn’t the same as the others. However, the reality of oppression or being intimidated and our struggles are congruous. I believe stories are written to connect tormented people. I wanted to let you know why and how I reached the ending in Redundant.

These days, we often hear people discussing “job satisfaction.” We aren’t happy about our careers, but why? Work that fails to make us happy is retribution. However, a day job serves our daily needs. We earn a salary that helps us sustain our living. Does a thick payment necessarily make us rich? Our requirements and our provisions are miles apart. Thanks to capitalism for cleverly maintaining that distance. People lying somewhere in between thrive on eating from the leftovers. It’s easy to unsettle them because these people are placed at the height of debacle. Under such circumstances, the party promises—sunny days ahead! Thus, the rulers continue to govern, and the tradition supports me to conclude my short novel.

KS: “Shubho himself felt embarrassed. He also felt a little pity for the man. A man who has lost everything; perhaps has no one to call his own. When someone drowns, all that remains is a story around him. No one thinks it necessary to check the veracity of that story. He thinks about his mother and that pui shaak she lovingly cooks for him. Perhaps this man doesn’t have anyone to cook lovingly for him anymore. He should have given her edible greens to this guy. Shubho shakes his head in disbelief—has he gone crazy? Compassion doesn’t sell in the city.” It’s challenging to retain the cultural nuance in translation, especially when the source text bears a rich artistic tone. Did you ever wonder how the English-speaking audience, especially the overseas readers, would feel the delicate texture of the climbing spinach that typically suits the Bengali palette?

BC: Rendering literature in another language translates the cultural essence for the target readers. No doubt it isn’t easy. The customs develop an individual’s mind frame. So, when someone solves a text, the traditions or the values get translated. Honestly, when I write a story, I don’t think about how the readers will accept the lifestyle in translation. When I read Russian literature as a teenager, I struggled to understand the stories. There were phrases I didn’t apprehend at all, but I derived the flavor using my ingenious vision. When we watch a foreign movie, do we understand every bit of it? Despite the subtitles, we often extract inklings from the script.

KS: There is limited space for criticism in contemporary Bengali literature. However, your translated (English) fiction has received more praise than your Bengali books. Must it be frustrating for you as a vernacular writer?

BC: We have a perfect quid pro quo arrangement in contemporary Bengali literature. To a certain extent, the same is true with Indian English writing. You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours? Isn’t that convenient? However, such reviews neither benefit the authors nor do they help readers pick up the right book. Therefore, I believe if Bengali literature is to survive for a thousand years more, we need venues that would allow space for real critiquing beyond the realm of fake praises and paid reviews.

KS: In the name of honest or balanced criticism, do you think reviewers often air their pre-conceived notions about the authors?

BC: Reviewers may have reservations about some authors, which shows when critiquing their work. They tend to ignore the positive elements and place themselves above the authors. When I watch theater, I deliberately criticize the actors. I think it stems from my inferiority complex. I wanted to be an actor, and my failure aids in slamming another actor’s hard work. Tagore had his share of negative reviews when he was alive. But if you ask me the names who belittled Tagore, I can’t remember them.

So, when I read a book review (be it candid or crash), I try to gauge the motive of the critic. As a publisher, I’ll cite a few examples. A critic wrote nasty comments on two books we launched last year: Hesitancies by Sanjeev Sethi (July 2021) and Collegiality and Other Ballads: feminist poems by male and non-binary allies, edited By Shamayita Sen (May 2021). The reviewer is a creative writer who has authored a few books. While discussing Hesitancies, he likened Sethi’s poems to Instagram Poetry. Sethi is one of the finest Indian poets, widely published overseas. Some of our readers asked me to refute his claims. But I didn’t. When a reviewer—a Bengali and aware of the legacy of literature—finds Instagram’s influence in Sethi’s verses, he is clearly unaware of the Bengali poet Abir Singha, much known for his short poetry. Being a Bengali, I’m ashamed of the reviewer for not doing his research before conveying the wrong message to the readers. On the other hand, the same reviewer described Collegiality as a publishing gimmick. When I read his comments, I laughed at his malice—what’s wrong with him? Is he a slave of the corporate domain? Can anyone discriminate against the movement for equality based on the gender of the protesting voice? But, it happens—it occurs daily to ensure business. I think the reviewer has not learned communist sociology, which emphasizes the liberation of human beings regardless of gender. Else, capitalism would rule society. Can you explain why a lady must buy branded nail polish on Women’s Day? Can you also tell me why a girl would be glued to a guy if he wears a specific deodorant? These derogatory television ads threaten the core concept of Feminism. Dramatist Supriti Mukhopadhyay used to advise us, “Keep your best work against each wrong motion.” So, when I read biased reviews, I laugh and move on. Because at the end of the day, I have to focus on new work—the best is yet to arrive!

Kiriti Sengupta, the 2018 Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize recipient, has poems published in The Common, The Florida Review Online, Headway Quarterly, The Lake, Amethyst Review, Ink Sweat,and Tears, Otoliths, Outlook, Madras Courier, and elsewhere. He has authored eleven books of poetry and prose; two books of translation; and edited eight anthologies. Sengupta is the founder and chief editor of the Ethos Literary Journal. He lives in New Delhi.