You Run, Darling: Mark Doty’s Deep Lane

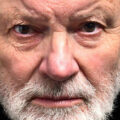

Mark Doty is tenacious in his in his examination of life and endlessly fussy about his use of words. He makes sure to convey his meaning, whether in the criticism of personal attachment or the depiction of youthful sexual realization. In his poetry in particular, Doty dials those qualities up. These traits positioning him in the same camp as CK Williams, Stephen Dunn, and the tremendous Robert Hass—poets who labor just below the line of the metaphysical, grounding their examinations of the existential life in tactile detail and the natural world.

Even among this esteemed crew, Doty’s work is characterized by the creation of small inner worlds and the scrutiny of life with notes of resignation, all presented in a muted Brock-Broidian language that provides the mortar for fireworks in those more placid passages. Perhaps the most exceptional thing about Doty’s new collection, Deep Lane, however, is that the poems breathe, the ones more akin to country gardens than fenced-in yards. The poems in Deep Lane reach toward transcendence while remaining tethered, however delicately, to corporeal reality.

Deep Lane

by Mark Doty

Hardcover, $25.95

WW Norton, 2015

The collection’s title reoccurs throughout the collection, giving it a strange rhythm, serving to create a kaleidoscopic vision of what these small moments aspiring for the intangible might add up to. In the second poem titled “Deep Lane,” Doty’s dog pulls up one of four stakes marking a new grave site. Instead of replacing the marker, or scolding his pet, he watches it run wild through the graveyard, thinking to himself, “You run, darling, you tear up that hill.”

The transcendence of beloved creatures like dogs, as well as that of those scorned ones, such as ticks and mosquitoes, are each observed with equal care. Transcendence means freedom, and a lack of regard for things that weigh humans down. In the sixth “Deep Lane” poem, Doty remarks, “if you don’t hold still, you can have joy after joy, / but you can’t stay anywhere to love.” More than anything, the collection is interested in the limits of freedom and how those limits hinder people and allow them to grow. Ultimately, the kaleidoscopic view of the many “Deep Lane” poems suggests that total freedom lasts only for a few brief moments, experienced personally or vicariously.

Tangential to Doty’s concerns about acceptance and struggle, there is an elegiac element to many of the poems, either in their tone or procedure. In “The King of Fire Island,” Doty spends seven pages ruminating on his time spent on the former gay haven. He reflects on the time a deer appeared at one of their soirees, using it as a jumping-off point to explore that time in his life. Here, the poem moves through Doty’s signature descriptions—first of the deer, then of contextual details—slowing the work down, imbuing it with the sense of mourning in slow motion:

In the distance the party thundered,

Season climbing to its apogee,

big speakers dragged out to the shore

where midnight lapped the snow fence

and dreamers swayed or danced,

held one another or themselves

The word choices sharpen and slow the work down. The party “thundered,” speakers “dragged,” and midnight “lapped” at a “snow” fence—the great trochaic sense of these words serving as a bramble to the reader, road bumps that force the work to be savored and lived in. The softness of words like “season,” “shore,” “fence,” and “held” work to echo the gentle sounds of the deer that serves as the anchor of the poem, the sounds of high grass, crunched branches, and the wind blowing through the natural world.

“The King of Fire Island” serves as the gateway to more directly elegiac poems, beginning with a sequence that explore the death of Doty’s mother. One is inclined to see the poem as the buffer between youth and experience, a sort of lifting of the veil and ushering in an understanding of darkness. As with all of Doty’s work, the answer is more complicated then that: his elegy sings with nuance, in shades of stinging pain and gentle acceptance. In “Little Mammoth,” the first poem to touch on his experience with losing his mother, Doty imagines his birth as that of a small elephant’s. There’s an inherent sweetness to the poem, even in lines such as these:

Mother’s milk in my belly

and a little of her shit, too,

so that I might eat.

of the sour-green steppes

that opened endlessly

before me, though not long

after I slid into sunlight

Visceral elements like fecal matter, a layer of fat, tusks in the process of forming, all work to highlight the idea of the mother as creator and erstwhile nature goddess striking a note of melancholy in the final lines: “and I am still one month old, and / forty thousand years without my mother.”

In “Apparition,” his mother’s disembodied voice begs for absolution, a painful moment that Doty connects to the natural world, the mundane act of carrying compost down from the top of the garden. The seventh “Deep Lane” poem recognizes his mother as a garden snake, teasing out the qualities that made her so indispensable to Doty by comparing them to the reptile’s own sensibilities. Here, there is no pain, only a complacent tone that seems relieved to have reached such emotion:

If I dose myself she won’t care, she wants me

to be happy, she wants me to take

the course I take. She stands

in a perfectly neutral relation to desire,

like a star.

These small moments of pleasure and transcendence hew so close to nature that one cannot possibly exist without the other. Reading Doty’s poems is like watching a deer drink from a lake: if you’re not still enough, if you aren’t listening, the moment will collapse around you, fleeing into the undifferentiated brush, ushering you back to life.

After carefully juxtaposing the natural world with the inner life, using those juxtapositions to set scenes, pivot around, and comment on mortality with, it’s no surprise that the collection ends with a short poem of celebration concerning a tree. “Amagansett Cherry” practically sings from the beginning, to the tune of a religious hymnal or American victory march.

Praise to the cherry on the lawn of the library,

the heave and contorted thrust of it.

Here, the praise is directed at what makes the tree unique, and, perhaps, even ugly. After traveling down the deep lane, the reader finally reaches a point of light. It turns out that what one lacks in transcendent beauty is also a cause for jubilation—or as Doty’s cherry tree explains,

Prefer it unbent?

I have no use for you then,

says the torque and fervor of the tree.

About Eric Farwell

Eric Farwell is a graduate of the MA program at Monmouth University in West Long Branch, NJ. His writing has appeared in places like the Rumpus, Prefix, the Aquarian Weekly, Electric Literature (forthcoming) and the Aleola Journal. He's currently applying to PhD programs around the globe with hopes of teaching at the college level.