Women Writing in 21st Century Brazil: Experimentation and Narratives of Self

There were days when Dita hid all the papers

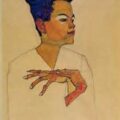

(Ruth Ducaso/Luciany Aparecida).

Brief considerations on writing by contemporary women authors

I start this essay with the opening words of a book written by a woman author, Luciany Aparecida [1]:

Prologue

One day, I decided to write.

To me, this phrase embodies something present in all writing by women. Between the lines of an apparently simple opening, we might read: I had the desire to write what I feel, I had the courage to show what I think, or I became impulsed to have a public life. Epitomised in the words “I decided” is the attitude of having control of one´s own life, one´s own will, one´s own destiny.

A few days ago, I listened to an incredibly moving recording of the poet Ana Cristina César [2] .It was taped at the last lecture she ever delivered, six months before she committed suicide. Her talk included a discussion of her own writing and its relationship to diaries and letters, two of her passions and elements constantly present in her writing practice throughout her life. One of the reasons this recording moved me so much was that it was part of a course called “The Literature of Women in Brazil” (“Literatura de Mulheres no Brasil”), a title evoking a literature we continuously emulate and against which the dominant misogynistic literary environment continuously reacts, in an apparent attempt to diminish its significance and aesthetic value.

There could not be a more emblematic example of how writing by women is devalued in Brazil than a recent case involving Ana Cristina César herself. Writing in Brazil’s most widely read newspaper, Folha de São Paulo, about the homage to Ana C. at the 2016 Paraty International Literary Festival, one of the country’s most important literary events, the critic Felipe Fortuna described her work as “minimal” and unworthy of any recognition whatsoever. His article belittled the importance of Ana C. in the national literary scene, comparing her to other writers who had previously honoured at the same festival, implying that she has no place besides writers such as Guimarães Rosa, for example. He labels Ana C. as inferior and insinuates that she was a “constructed” writer, a myth forged out posthumously by her friends. In a tone of misogyny and conservatism, Fortuna writes:

In fact, the construction of the literary figure of Ana C. is entirely posthumous: the guardians of texts taken from drawers, folders, and trunks recognize the weakness of her material. In a biographical outline [of Ana C.] by Italo Moriconi, one of the books published during her lifetime, Cenas de Abril (1979), was considered “adolescent catharsis.”

Fortuna’s entire article is a misogynous challenge to the literary merit of this poet. He goes on to add that literary significance can be measured by the quantity of work produced by a writer, a statement even more shocking when we consider the number of male Brazilian writers with highly sparse production who are praised by critics rather than belittled. For example, despite only having published three books (a novel, a book of short stories, and a novella), the writer Raduan Nassar is worshiped by critics. But if he were a woman, the story might well be different.

Much of what I will say here is nothing new. It’s one of those mantras we spend our whole lives listening to. Perhaps the novelty, in addition to the specific women writers I bring to this discussion, is that I make use of Ana C’s speech for critical-theoretical support. The reason I want to emphasize, engage in, and draw upon her brilliant reflections on poetry, writing, life and art, is that—unlike the critic cited above—I believe that both her poetry itself and her thoughts on literature are highly relevant contributions to be heard alongside other strong female critical voices in the arts. In other words, given that in the field of criticism the predominant voices are male and that women rarely have opportunities in the few “official” mediums of criticism, we need to actively seek out opportunities such as debates, lectures, reviews, talks, blogs, letters, and other spaces where women can successfully challenge machismo.

In the recording, Ana says that her poetry is deeply linked to diaries and letters, as many critics have noted. She says that this is no surprise, given that “women enter the writing scene from a starting point of this intimate, domestic, personal place.” It is interesting to bear this in mind when considering that, rather than becoming conformist and/or writing within the logic of the canon, Ana Cristina Cesar was a key reference for experimental writing in the 1970s. One of the principal writers of marginal poetry, she was among the first poets in Brazil to introduce cuts, abrupt line-breaks, and fragmentation in her work and was one of the first to dissolve and decentralize the poetic subject to reveal ordinary daily life, using small gestures represented in her desacralizing poetic themes.

So, how have diaries and letters—genres traditionally seen as “lesser” forms of writing precisely for being associated with women and with “non-artistic” fields—provoked this aesthetic and symbolic impact on the writing of one of the most emblematic poets of experimental literary writing in Brazil? And, how do these elements continue to influence the writing of hundreds of other women writers today? These questions are answered by Ana C. herself, in her enigmatic recorded voice: diaries and letters, she says, are the genres “of secrets, of revelations, of the wish to open up to someone, to place oneself in front of the other.”

This writing, these women, this sex

Luciany Aparecida, a Brazilian author born in the dry sertão backlands of the northeastern state of Bahia, started writing in secret on a borrowed typewriter and wrote for years before sharing her texts with anyone. In an interview conducted via email in June 2016, she told me:

(…) when I used to write without telling anyone, I never gave any thought to the idea of whether I was a man or a woman…. It was just so huge in my mind that writers are always male, white and dead, that I never even considered that what I was doing was writing, or that it could be literature. I used to write … with the feeling that I would die if I didn’t… I would write and write every day, in secret, and I hid all my notebooks…. I hid them for various reasons. maybe we can consider that one of the reasons was because I was a woman and that writing was therefore a mistake (given that writers are/were male, white and dead). (…) what I mean is that I saw myself as a woman in the senses of real life and of work, and also in writing, but not as a writer, not as someone with the social freedom to assume a text … maybe to some extent because I was experimenting with texts with a different kind of feminine demand … well … I think I saw myself as a woman based on a relationship with sex, feminism based on sexual freedom telling me … told me … and then Hilda [Hilst], Clarice [Lispector], and Helena [Parente Cunha] who touched on these issues, helped me in this process of seeing myself as a woman … in the contemporary scene, many women writers (Conceição [Evaristo], Verónica [Stigger]), and my own writing, have helped me see myself as a woman writer. What I mean is: the woman as a writer needs to pass through this whole maze, it’s a game, it’s a scene, it’s work, it’s a conjugation: Look, I write, let me speak over here! Men don’t get that … he writes, and that’s it. Let’s listen to him?! [my italics]

The book consists of a hybrid text alternating in structure between verse and prose and between first and third person. The text uses non-standard punctuation and mixes genres such as poetry, prose, drama, and fiction and is divided into sets and sections. The first of these is:

Thevagina (sic)

I ran my hand along my sex so the bliss wouldn´t end, scared, I lost the climax (arousal on discovering a slit between my legs)

The desire was so sharp that my stiff pendulum made me think I was a man.

—What bliss (stand up)

—Today will be a good day (stand up dream)

Dita came when she was writing.

Poetry turned her on so much that the back and forth was enough to get her going.

Sitting still after climaxing, she was serene.

Then, when Nei appeared on the scene, she extended the rhythm of the verses.

Strong sexual expression evokes a link between pleasure and writing, causing us not only to consider the erotic relationship associated with the act of writing itself and with the book (bringing to mind other authors such as Freud and Clarice Lispector) but also suggesting a kind of irony and stylization in brute contrast to masculine power. An aesthetic of sexual elements usually representative of the masculine is here used by the female subject, now in control of her own pleasure and her own writing. When Judith Butler distinguishes gender expression from gender performativity, she allows us to see the complexities of gender and challenges us to perceive the relationship between gender and sexuality as a relationship constructed through social practice, as an existence not only elaborated via notions naturalized through repetition, but also of discontinuity: “if gender attributes and acts, the various ways in which a body shows or produces its cultural signification, are performative, then there is no pre-existing identity.” When I read the phrase The desire was so sharp that my stiff pendulum made me think I was a man within such a framework, this performativity serves neither to affirm the feminine nor the masculine, but instead affirms a trans sexuality, able to exercise both positions, with the masculine being a reference to the power possible in this body that is not a “man.”

Between this “explicit secret” of writing and the diary genre, there is much common ground. Reflecting on the importance of diaries and letters in her work, Ana C. reminds us that throughout history women were only permitted to write diaries and/or letters. With letters, there is a recipient: the subject tells something to somebody, speaking about herself or about others, about her feelings and daily life; the diary meanwhile is also a confession of self, a place where things can be told without censorship, subjectivities can be freely expressed, and narratives of daily life are shared.

The diary may or may not have a real recipient, but on a metaphorical level there is always an abstract reader-recipient figure, the subject who writes and the subject who listens. When Ruth Ducaso / Luciany Aparecida says “One day I decided to write” at the beginning of her unpublished book Florins, she appears to be writing in a diary, telling secrets that include her sexual desires and practices. The reader is effectively presented with a subversion of genders. Ivia Alves, analysing Bahian women authors from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, affirms:

It is not only that they (women) break away from social rules. In their literature they also courageously construct this counter-discourse. And what is a counter-discourse? It is the idea of non-acceptance of social norms or the dominant discourse and the construction of another discourse to replace it, either through confrontation or through questioning of these limits.

Luciany Aparecida´s writing is an inheritance of writing by women who broke away from the dominant discourse: a discourse still surrounding woman writers in today´s literary scene. And this writing brings the reader back the place of the secret, the confessional, and the women writing letters and diaries, subverting the place within the place that is their own writing. Choice of language and themes is also a part of this subversion, this seizing of freedom, and is effectively sexual performativity, distributing desire, pleasure, and power within gender relations. This is writing that provokes a deep sense of estrangement. This is queer writing.

The qualities of queer writing are evident in the work of many Brazilian women writers. One such example being Angélica Freitas [3], one of the most important poets of her generation, who makes womanhood the central theme of her book, Um útero é do tamanho de um punho [4]. The poems could be considered feminist, full of wry, caustic humour that also reveals the arbitrary nature of the construction of the feminine and the machismo surrounding the woman.

Among the book’s themes are abortion, norms of beauty, lesbianism, sexual freedom, and the transgender body. The poem “woman after,” for instance, deconstructs and denounces social and family control over bodies and subjects:

dear mom and dad

I’m writing from thailand

it’s a fascinating country

it even has elephants

and some great beachesbut I’m here for other reasons

although I love tourism

dad, remember when you used to say

that I looked like a gal

and mom asked: please could you stop that?well now I’ve become a woman

I had an operation and became a woman

you don’t need to accept me

you don’t even need to look at me

but now I’m a woman

In this poem in the form of a kind of “letter” from the persona to her parents (reminding us again of Ana C.), Angélica Freitas evokes tension surrounding a socially unacceptable gender performance. It offers a fascinating revelatory human dimension of the journey undertaken by the transgender body in order to “fit” into the female identity that is affirmed by the persona while being repudiated by society and her family. The aesthetics of the poem provoke reaction and emotion as well as an “experience” of estrangement and contrast.

The end is even more visceral within the poem’s false levity if we consider the effect of the word “elephant” at the beginning: this heavy animal brings something of the absurd, and the subtle presence of the adverb connector “even” (there are even elephants) creates a direct relationship with the transformed post-op transgender body. “Thailand,” where there are even elephants, also has this body, now a woman, revealing herself, presenting a confessional and positioning herself in front of her parents, who had previously viewed her as absurd, as an exotic, heavy elephant in its own habitat. It is from the country of the “elephant” that this other, newly liberated body, writes the letter in order to confront those who opposed the persona’s very existence.

Angélica Freitas’ work is unique, conforming neither to forms nor conventional expectations of heteronormativity and poetic tradition. Her writing takes structures and devices from other poetic spaces such as letters, which she appropriates to create singular and challenging poetry in a contemporary aesthetic proposal with astute topical themes and a refined use of irony and satire.

Stories of self, writing by women, and non-universal literatures

Writing by contemporary women has this extraordinary power, not in spite of, but precisely because of the fact it brings to the reader—whether by the author’s choice or necessity, the place of the woman, the feminine. It’s a place defined by performativity in writing, memory, challenges to form, vindication of the right to write, or simply by a desire to narrate oneself or expose the feminine bonds to which the author is linked. This feminine place is frequently drawn upon by contemporary women writers, whether as a way of beginning a new phase or a way of entering a new social space for these plural femininities. It’s expressed in many forms, such as in vocalizations of non-acceptance of sexuality, vindications on questions of race, conversations about the desire of the author to recognize herself as writer, and development of artistic and aesthetic paradigms for expressing individual worldviews.

These develop within the contemporary scene not as models in relation to the woman or the feminine, but as statements of the right to difference. Difference in relation to what is male, heterosexual and white, and also difference in relation to other women. They’re generated by the act of writing as a political action, which may or may not be explicit, but that appears when the text calls for any kind of female voice. Even when women authors question or re-elaborate memories, the act becomes a political and aesthetic. These narratives of self may be a way of addressing at least part of the story in which they establish themselves. Butler, on the writing of self, says:

If one is speaking in giving an account of oneself, then one is also exhibiting, in the very speech that one uses, the logos by which one lives. The point is not only to bring speech into accord with action, although this is the emphasis that Foucault provides; it is also to acknowledge that speaking is already a kind of doing, a form of action, one that is already a moral practice and a way of life. Moreover, it presupposes a moral exchange.

Ana Cristina César, whose voice I hear as I write, says her poetry became ever closer to diaries and letters not only because of the gender element, but also because her writing gradually became a confessional, a place where peers would hear what she chose to reveal, a place for whatever did not need to remain only in letters and diaries. In this sense, in the context of Butler’s explanation around the narrative of self, black women authors from Brazil such as Lívia Natália and Conceição Evaristo write as though specifically addressing their peers, with no interest in having their work moulded or judged by white hegemonic society. In their texts they construct narratives of self, their places as black women and women writers, proposing new aesthetics and new ways of telling. Numerous aesthetics and forms are employed by black Brazilian women writers, and I want to highlight just two examples.

In her short story “Eyes of Water” (“Olhos D’água”), Conceição Evaristo (b.1946) details the story of her mother, intertwined with her own life story:

And that night, the question continued to haunt me. It had been years since I’d left home in search of a better life for me and my family: she and my sisters had stayed behind. But I had never forgotten my mother. I recognized her importance in my life, and not just hers, but also my aunts and all the women in my family. And also, already at that time, I chanted songs of praise to all our ancestors, who came from Africa ploughing the land of life with their own hands, words and blood. No, I will not forget these women, our Yabás, the owners of so many wisdoms. But what color were my mother’s eyes?

By bringing her ancestry to the text, by evoking a storytelling tradition as well as referring to the women in her family and to her African ancestors, Evaristo adopts a political identity and suggests a constructed self. More than mere decoration, the Yorubá word Yabás—meaning “Queen-mother” and used to represent the Orishas Oxum and Yemanjá in Candomblé—links the narrator to her African heritage and to that ancestral memory, from her mother’s eyes to the women in her ancestral line.

Along these lines, the poem “Where the mirror? –For my black sisters” (“Onde o espelho? –Para minhas irmãs negras”) by Lívia Natalia (b.1979) directs its poetic voice at the reader/listener not only in order to be heard, but with a sense of wanting to place itself within a collective. The poem wants to lend its voice to other women and to assume black sisterhood as an principle of deconstruction within a hegemonic racist society:

This hair you straighten over your kinky hair,

is the unfortunate impression of what you are not.(When dressing in the skin of the enemy

what is silenced in you and what is lost?

How many animals do you know

who do this as mere reaction?)This hair is heavy and broken over your kinky hair.

You wear it as an impure mantle

stifling the curled blackness

folded in on itself:

philosophical.Wires hardened like beaten horses,

cry with the morbidity of this breastplate

and you are masked as white.This hair, scorched and grotesque

buries what is most beautiful in you

The curl is also a way

of Being.

This poem is structured as a dialogue/monologue in which the poetic persona gradually deconstructs the notion of women submitting themselves to artificial hair straightening in an attempt to appear white. The poem’s complexity is revealed subtly through changes in rhythm and tone. For example, from the opening reprimand, This hair you straighten over your kinky hair / is the unfortunate impression of what you are not, the poem leads its addressees—the black sisters and even perhaps the poetic persona herself—through this multi-layered mirror game and the conditioned aspiration to become a caricature of the oppressor. The poem functions as an expression of the struggle to reaffirm both external and internal enemies within this struggle against a racist society.

The verses play themselves out as if in a physical place with opposite sides, where “the women with kinky hair” are called to account for this denial of their own features. The suffering associated with the transformation reveals an intense discourse on the pain of not being valued or recognized because of kinky hair. The symbolism of the mirror suggests self-reflection, leading her to the state of Being with a capital B. Recognizing the full beauty of “Being” black, the beauty of this black woman and her kinky hair acquires a philosophical, dense, and powerful dimension.

Experiences in writing the experiences of the body: an “expanded” literature

In dialogue with critics such as Josefina Ludmer, Florencia Garramuño, and Natália Brizuela, Luciene Azevedo writes on the “inspecifity” of literature within contemporary literary criticism, considering what is known as post-autonomous literature:

By dissolving the conditions that established autonomy in modern art, contemporary art subscribes itself to an inspecifity, complicating the previous certainties where limits were established between fiction and reality, life and art, author and narrator, art and non-art.

Luciene Azevedo’s discussion challenges a criticism field accustomed with a set idea of “the literary.” The hybrid writings of Laura Castro (b.1980) and Karina Rabinovitz (the latter in partnership with visual artist Silvana Rezende) present unique and distinct aesthetic proposals within this expansion of the idea of the literary.

Laura Castro is the author of the book-object Cabidela: the Notebook of Masks (Cabidela: bloco-de-máscaras), a work comprised of texts originally published on the author’s blog over a three-year period. The physical book-object, developed in partnership with the designer Cacá Fonseca, consists of four elements: a novel (“Breu”), a notebook (“Borratório”), a deck of cards, and two masks. The composition both marks and dissolves the frontiers between genre and medium. It both is and is not a transposition from the blog format to the medium of paper. The liquidity of the internet, the mobility of a screen with scrollbars, the way a blog is organized in posts, the images, colors, comments, etc., could not be transported. The result of its transformation onto paper brings new considerations about art and reading in contemporary society.

Since Cabidela is a novel as well as a blog, it also has the characteristic of a diary and notebooks. Rather than imitate the resources of technology, it adopts a handmade, DIY aesthetic. The book-object is spiral-bound in handcrafted paper, accompanied by notebooks made from bread-wrappers. Sewn together by hand, the set contains masks and a deck of cards, forming a game with elements of dramaturgy, theatre, and staging. The dates and order of the blog were re-worked and the texts were re-organized to allow for a number of different interpretations. In this format, each reader is invited to experiment via their own relationships and attitudes. The “expanded” experience is provoked by the relationship with both the internal and external elements of the novel.

The novel is not exactly linear, even though the pieces, the “letters,” come together to form a coherence. Additionally, this writing, within contemporary aesthetic discussions and inspecifities, represents a woman who writes and who touches on discussions of the feminine place; meanwhile, the woman character engages in “writing herself” within the novel. Thus, author and character dissolve into each other through the staging of the writing, as in this extract from the blog:

I came back. I opened the drawer that had become a wardrobe. I unwrapped the fleet of paper boats. I decided to transcribe everything in pen. But these loose papers didn’t have a route. They went around in circles for sure. Around the navel, said a superego. No, sir. I suppressed this part of the text so Edith wouldn’t shout at me again and say that I wasn’t a real novelist. In truth, she told me this while holding down her glasses a little to stare at me, emphatically. Getting back: I began like that, finishing. I took out the costume of the character—that is me—and began to narrate. This was coming out of the drawer: making myself naked, exposing myself to diagnosis.

Everything is written here, on this roll of paper, in pen. It is the portrait of the artist as a young woman. It is an entire page and that is all. It is a tangle of threads. A novel isn’t a ball of string anymore, I try to explain to Edith. They won’t allow it, she says, in a judgemental tone, they won’t let you through. They who?

at 10:21:00

drawer syndromeI chose the pen to start with. It was no longer time for charcoal, eyeliner, crayon, or scrawls. It was time for the definitive. What would remain without my body, without my fist. The voice in pen. I was afraid of this eternity. All these years I had been afraid to come out of the closet and say: It´s me the writer, the actress who stages texts in real time, the narrator of notebooks, sailor girl only in carnival blocos. But why explain? Who would listen? Insomniac copywriters in a googlistic late night of work? It´s like this: I ask, I ask, I never finish. He says: it’s uninterrupted. Uninterrupted, I stopped, abrupt.

às 10:14:00

[exact blue envelope]Luísa,

I know they are going to get me out there. You must be asking yourself who? I say: the dogs. Even so, I will publish this.

(…) Read this however you want. Open it randomly, from one side or from the other, begin when you finish, finish when you begin … in any manner, it will be me here, in pieces, missing. I don’t know when I will be back, if I will be back one day. But I know that here, I will stay. A kind of survival, you know what I mean?

Castro’s writing carves out the feminine place of a writer while simultaneously raising questions about the “death of the author” as the “narrator-character” fictionalizes her surroundings to such an extent that she ends up depicting reality. The work also raises questions about the breaking down of borders, mediums and genres, and opens itself up to another critical—and uncertain—space: that of reception, publishing, and encounters between publisher and reader.

In another strand of this “expanded literature,” the poet Karina Rabinovitz (b.1977) uses multi-media language to experiment with writing spaces and to appropriate elements and processes from other areas art genres, most notably the visual arts. In partnership with the artist Silvana Rezende, Rabinovitz created a unique book-object as part of a multi-space, multi-media, multi-aesthetic, multi-art object entitled The BOOK of Water (O LIVRO de Água).

The work constituted a series of installations in the Museum of Contemporary Art of Bahia that includes notebooks, photographs, audio recordings of poems, interactive multimedia, performance, and the book itself: a collection of loose pages with images of writing to be read in any order. Here is one poem from the “Livro de Água”:

The truth is

I never

left that swing

in the square of that

island

where we used to spend

ends of afternoons,

me and my mother.

Photo credit: publicity/artists’ collection

Projection of words on the body, entitled “banho” [“bath”]. Photo credit: Karina Rabinovitz and Silvana Rezende/Artists’ collection

Photo credit: Karina Rabinovitz and Silvana Rezende/Artists’ collection

Photo credit: Karina Rabinovitz and Silvana Rezende/Artists’ collection

The synasthetic proposal of this “writing” is extremely intricate. In certain respects, it demands a highly discerning contemporary reader. Yet the work is equally accessible to every reader, from veteran museum-goers to a child sitting on the swing installed in the museum listening to poems in Karina’s voice through headphones. Each page of the book-object contains an image-poem with colors, textures, and different forms, in an attempt to reproduce the experience of creating the work.

This represents a complex conceptual project. It intervenes in various ways with the literary and artistic fields, while providing a radical experience that ruptures the difficult field of reception, of the meeting with “the” or “a” reader.

The book brings the element of the feminine through the poet’s presentation of her own subjectivity, offering handwritten notes in a reference to her own story of writing, traversing notebooks and the body. The writing advances on itself, expanding, extrapolating measures of limitation, aesthetics, and place. The writing seems to revolutionize all its own places: the symbolic, the physical, the literary, the artistic, the place of reception, and the place of poetry.

Conclusion: Ourselves as readers of our own writing

Keeping in mind the persistent history of struggle that continues to advance and transform society on so many levels, I find that women writers, in addition to adding value to the world of art and provoking varied aesthetic experiences—distinct from one other and distinct in relation to the experience of men—install a sense of liberation in the reader and, more specifically, in the woman reader.

There is an invisible political action on both sides: the woman who writes with sensibility about a black woman’s hair; the woman who writes from a transgender body; the woman who writes of her sex; the woman who reveals the secret of being a writer; the woman who tries to erase her own writing; the woman who frees herself; the woman who… (etc.). There are endless possible themes and they join together with thousands of women readers, who in turn bring to their own lives the symbolism of this personal experience of reading, altering their own position as subject and provoking a political shift within their own geographies.

Feminist criticism must be conscious of this dynamic. We must engage the potential of such writing and help transform the thorny ground of machista culture—a culture which, when it becomes impossible to impede the presence of women, tries at all costs to minimize their significance and the effect of their artistic work. They tried to do this with Ana Cristina César at Flip in 2016, and we can recall all too well how they also tried to do this with the Simones, the Amélias, the Clarices, the Zoras, the Sylvias, the Gertrudes, the Carolinas de Jesus of the world…

But for all this, here we stand: women readers that we are.

[1] Luciany Aparecida’s books are as yet all unpublished. Her writing has been awarded grants and prizes on state and national levels in Brazil and has appeared in anthologies. She writes using three different heteronyms (although she herself does not use this term, I use it here for lack of a more appropriate word). The three are: Ruth Ducaso, Antônio Peixôtro, and Margô Paraíso, and occasionally she also writes as Luciany Aparecida, in experimental, performative literature, with a strong presence of women and transgender characters. Her writing has a surprising literary force and her female characters deviate from the norm; in general they are sexually free, strong and complex. Sexuality and sex are key features in the writing of Margô Paraíso and Ruth Ducaso. With a desire to delve into the obvious peculiarities of her work, I started carrying out interviews with the writer via email, and in the first round I asked questions about her writing, her literary references and her writing methods of those of her heteronyms.

[2] Ana Cristina César (1952 – 1983) was a Brazilian poet and one of the most important poets within marginal literature of the 1970s in Brazil. She is often referred to as Ana C.

[3] Angélica Freitas is one of the most important poets of her generation in Brazil and is critically acclaimed both in and outside Brazil. She is the author of the poetry collections Rilke Shake (translated by Hilary Kaplan, Phoneme Media, 2015) and A uterus is the size of a fist (translated by Hilary Kaplan, forthcoming). Her work occupies a unique place in contemporary poetry, with marked irony and use of humour as poetic devices drawing in the reader with themes of day-to-day acts, inspiring either a sense of identification or discomfort. Her command of rhythm, and her skilled deconstruction of the notion of poetry occupying a sacred place, a kind of anti-lyricism, and her evident critical take on how women are placed in the misogynistic world, are highlights of her work. Outside of Brazil her work has been published in English and Spanish, and in the United States, Rilke Shake translated by Hilary Kaplan (Phoneme Media, 2015) won the Best Translated Book Award 2016 and the National Translation Award 2016 (American Literary Translators Association).

[4] A selection of poems from this book, translated by Hilary Kaplan, appear in Centres of Cataclysm – 50 years of Modern Poetry in Translation (Bloodaxe books, May 2016).

Translator Sarah Rebecca Kersley is a British translator and poet based in Brazil. Her translations have appeared in Two Lines: World Writing in Translation, Machado de Assis Magazine, Cadernos de Literatura em Tradução, and other journals. Her own poems have appeared in Revista Pessoa and O Globo. She is co-founder of Livraria Boto-cor-de-rosa, an independent bookshop and cultural space dedicated to contemporary fiction and poetry in Salvador, Brazil.

About Milena Britto

Milena Britto was born in Brazil and is a professor and researcher at the Federal University of Bahia. She is also a literary critic and curator. Passionate about literature from an early age, her work focuses on the contemporary, with particular interest in gender and queer studies. She regularly publishes criticism of contemporary writing, and has taught at the University of California at Berkeley and at Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Equador.