Weegee: Art, Craft, Murder, and the Legacy of Film Noir

The photographer Usher Fellig (1899-1968) earned the nickname “Weegee” from the apparently necromantic connection he seemed to have with tragedies of the night, garnering comparisons to the “Oujia” board (given phonetic spelling) and all of its inferences of dark psychic happenings. During the 1930s and 1940s, Weegee’s first-on-the-scene reliability at so many of New York’s more famous murder scenes, creating photographs just after the killing of mobsters such as Dutch Schultz, Legs Diamond, Waxey Gordon, and Mad Dog Coll, gave him the nom de plume of “The Official Photographer for Murder, Inc.”

The nickname stuck and the International Center of Photography has become the archival sanctuary for Weegee’s life’s work, housing over twenty-thousand prints and negatives, hundreds of film strips, and many of the original newspapers and magazines in which his pictures first appeared. A recent retrospective of his work at the Center was titled “Murder Is My Business.” The marvelous creativity of Weegee’s photographic art is that, while pursuing the purely functional role of the craftsman performing his practical duty, he imbued the antiseptic mimesis of the photographic image with high compositional and metaphysical stature.

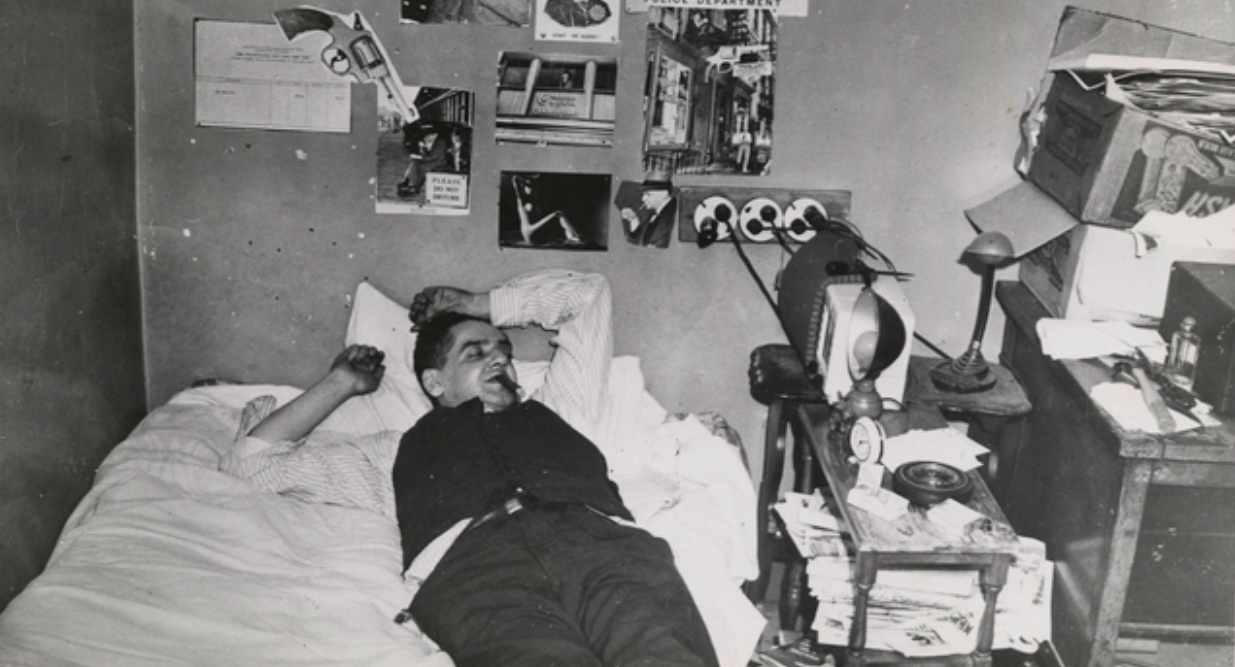

For Weegee, creating sublime visual art and taking a useable journalistic photograph blended seamlessly into one another. He kept fire and police department shortwave radios in his bedroom and car so that he would always be first on the scene of a murder, fire, arrest, or domestic violence. He had a makeshift photography lab in the trunk of his car to aid him in the process of putting his photographs into the hands of The Daily News, ahead of all of the competing photographers. He even bribed many police into giving him private access to what was known as the “perp walk,” the moment that an arrested suspect was led by handcuffs from the police van to the station house, a symbiotic ritual in that the cops who made the arrest wanted publicity for their good police work and Weegee naturally enjoyed the special access to very dramatic moments.

Photography is possibly an ideal growth medium for the longstanding dichotomy between esoteric art and fundamental craftsmanship. The super-realism of the photographic image sounded the death knell of the two thousand year old Western mimetic ideal of painting. We find that shortly after the invention of photography, the “real” is no longer the ambition of most serious painting, and we move farther and farther from concepts of reality with the Impressionists around 1860 and all who followed over the next hundred and fifty years. As the camera lens created astonishing glimpses into the physical dimensions of our everyday lives, canvasses revealed the inner laws and landscapes of our imaginations (Cubism; Fauvism; Surrealism; Constructivism; Dada; Futurism; Abstract Expressionism; Op Art; Pop Art; Conceptual Art).

Weegee generally does not garner too much serious academic criticism, mostly because a) he is often overshadowed by Diane Arbus—even though, despite great talent, her style is often derivative of Weegee’s—and b) he is still regarded as a journalist photographer who, in the opinion of his critics, only unintentionally crossed over into “art” photography. Today academia largely regards Arbus as the “sensitive artist” whereas Weegee is seen as the “Daily News Photographer Who Was Artistic.”

But look at the grouping in Weegee’s “Their First Murder”: the symmetry and drama are worthy of El Greco. The shock, the horror, the surreal, the degenerate, all the social elements that Weegee so poetically captured in the perfect moment, all of this formed the macabre texture of Arbus’ material as well, yet few people realize that she posed subjects to achieve her best results and often took numerous shots from similar angles (her “Child With Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park NYC” is an example). Both Weegee and Arbus studied professional portrait photography. Arbus worked with her husband for many years, as they earned their living with studio photography, while Weegee began as an assistant to a street photographer who did tintypes of children on ponies. Yet, significantly, the “prepared frame” and the posed photograph remained dominant in Arbus’ work; as suggested above, many of her very bizarre photographs, which appeared spontaneous, were set up in advance.

The uncanny element is that Weegee used the everyday to capture, with an unparalleled genius for spontaneity, the unsavory, the bizarre, and the surreal. Weegee was indeed a conjuror; his imagery possesses the lion’s share of incantatory power. I see no aesthetic hierarchy in the quintessential Weegee image: disposable newspaper photograph or archived museum print, his genius for infusing the aleatory with form and emotion gives his imagery an extraordinary power.

Weegee’s uneven career as a quirky conjuror of verite shock imagery is vividly demonstrated by his tendency to group images under headings for subjects he habitually covered as a free-lance photo-journalist (Lower East Side; Police; Fire; Sammy’s; Coney Island; Times Square; The Opera; War; Lovers; Harlem; Entertainment; Movie Theatres; The Circus; The Village). These and many other examples give full rein to the harsh dignity of Weegee’s poetic documentation.

The visual stratagem of the typical Weegee image is often contradictory. With free-lance photojournalism as a technical, professional, and social point of departure, Weegee fluidly combined very diverse elements of style and attitude.

There is the lurid opportunism of the pre-tabloid “shutterbug” nightly scouring city streets for mayhem, personal tragedy, and disaster: Manuel Jiminez lies wounded in the lap of Manuelda Hernandez. There is the stark lighting and shadow of contemporary film noir, heavily influenced by German Expressionist cinema, together with the omniscient point of view of the existentially detached, hard-boiled private eye: Accident on Grand Central Station Roof, 1944. In fact, I would venture to say that in as much as photography and cinema had a very dynamic relationship throughout the early decades of their development in the twentieth century, that many of these chiaroscuro, bleak urban locations Weegee captured contributed to the evolution of film noir.

The tendency towards location shooting in gritty city areas is certainly prevalent by the 1950s in many films by major directors such as Elia Kazan (On the Waterfront); Abraham Polonski (Force of Evil); Otto Preminger (Angel Face); Fritz Lang (While the City Sleeps); Samuel Fuller (Pickup On South Street); Nicholas Ray (In a Lonely Place); Joseph Lewis (Gun Crazy); Robert Aldrich (Kiss Me Deadly). Besides the dissolution of the Hollywood studio system and a maverick preference for the immediacy of urban location shooting, as opposed to controlled “artificial” studio shooting, much of this filmmaking and many movies in the ensuing decades were certainly influenced during the twenty-year (1930 to 1950) newspaper coverage of Weegee’s nocturnal urban nightmares. A television series based on realistic detective work, The Naked City, which aired from 1958-1963, based on the 1948 feature film of the same name, directed by Jules Dassin, could have wrung its stories from any of Weegee’s photographs, assimilating their standard of visual style, tone, subject matter, plus the look and feel of inner city reality that would be duplicated not only in future films but many more hard boiled crime-drama television programs (Dragnet; The Story You Are About To See; Crime Syndicated; Racket Squad; Gang Busters; Police Story; City Detective; The Man Behind the Badge; The Lineup; Official Detective; Harbor Command; N.Y.P.D.).

There is the spontaneity, pathos, and nonchalance of neo-realist settings such as alleys, side streets, lower-class neighborhoods, saloons, staircases, back lots: Sleeping at the Doyer Street Mission. There is the elegant symmetry and economy of drama in figure grouping reminiscent of Renaissance painting: Their First Murder, Oct 9, 1941. There is the sense of “filmic time” (as opposed to photographic time), where oblique angles plus the use of the frame comment on activity off-screen. This provokes an awareness of the overlapping occurrences within a given picture, pointing to the continuation of another world beyond the boundary of the traditional “well chosen” photographer’s angle: The Juggler, Lower East Side, 1940.

Throughout this confluence of effects and treatments, there is always the compassionate, empathic, spur-of-the-moment portraitist, fusing chance opportunity with razor-sharp intuition for pictorial cohesion, to produce glimpses of humanity at its best and worst.

Certainly this paradox of completely unstaged human events, and controlled spatial dramatization, is a key to Weegee’s art. The milieu of his profession obviously preceded (and very much influenced) his personal style; the kind of candid imagery gobbled up by the dailies which regularly purchased Weegee’s pictures was in vogue as a look, and an end in itself, many years before and after Weegee’s twenty year career as a free-lance photographer (1927-1947).

Weegee used the basic premise of reportage and objective commentary as a way of stylizing the ordinary: the undeniable “realism” of his pictures seems somehow infused with a touch of madness, the bizarre, the eccentric, the visionary, the formalized; yet the humanity and emotional voice of his strongest images always resonates. He was never a “formalist”; rather, he brings the formal into his pictures (chiaroscuro effects; odd angles; baroque blocking; off-frame references), turning it into a living entity, one that occurs with the same metaphysical velocity as the human story that generates it.

One troublesome aspect of his work is the shameless voyeurism. Besides a redundancy of image-making formulas—and many uninspired, simply bad pictures—there is the unsettling question of aesthetics versus ethics. Weegee himself commented critically on the public hunger for a steady diet of gore, yet he supplied it with ruthless professionalism. It remains to be seen whether or not the conflict between artistic license and personal privacy intrude upon the inner sanctum of “art for art’s sake.”

Speaking of an aesthetic barrier, which is inherent to cinema but can be similarly applied to photography, Orson Welles once said, “…the danger in the cinema is that you see everything, because it’s a camera. So what you have to do is to manage to evoke, to incant, to raise up things which are not really there.” Weegee’s art offers us such charms and powers of evocation. He wrestled away from photography’s mimetic possessiveness a poetry and a vision singularly his own.

About Peter Dellolio

Born in 1956 in New York City, Peter J. Dellolio went to Nazareth High School and New York University. He graduated 1978 with a BA Cinema Studies and a BFA Film Production. Dellolio wrote and directed various short films, including James Joyce’s short story Counterparts which he adapted into a screenplay. Counterparts was screened at national and international film festivals. As a freelance writer, Dellolio has published articles on the arts, film, dance, sculpture, architecture, and culture, as well as fiction, poetry, one-act plays, and critical essays on art, film, and photography. His poetry collection A Box Of Crazy Toys was published 2018 by Xenos Books/Chelsea Editions and Bloodstream Is An Illusion Of Rubies Counting Fireplaces was published in 2023 by Cyberwit/Rochak Publishing. He is working on a critical study of Alfred Hitchcock, Hitchcock’s Cinematic World: Shocks of Perception and the Collapse of the Rational, excerpts from which have appeared in The Midwest Quarterly, Literature/Film Quarterly, Kinema, Flickhead, and North Dakota Quarterly. His poetry and fiction have appeared in Antenna, Aero-Sun Times, Bogus Review, Pen-Dec Press, Both Sides Now, Cross Cultural Communications/Bridging The Waters Volume II, and The Mascara Literary Review, among others. Dellolio was a contributing editor for NYArts Magazine, writing art and film reviews.