Trans-Parency: An Appreciation of Mary Meriam

The following essay is adapted from R. Nemo Hill’s opening remarks of a reading held in 2023 to celebrate the launch of Mary Meriam’s collection Pools of June, for which Hill also served as publisher. A recording of the reading can be found on YouTube and embedded at the end of this piece. —Ed.

I told the world the story of My complicated love. —Mary Meriam

Sometimes we do not allow a poet the authority to work out solutions to complicated problems on their own, unless they’ve been granted that authority by some academy. The fact is—a true poet’s problems are most often of their own making, and thus the solutions can never be found by the application of any given formula. Poets working on their own, well outside the too-often tyrannical parameters of various schools and cliques and doctrines, may still encounter such challenges to their own authority via critical peer pressure. Many simply fold their cards, either leaving the game or submitting passionlessly to its rules. Few endure—and, like Mary Meriam, blossom.

Ok, that’s all quite a mouthful. And dryly loaded terms like “the academy” and “poetic authority” may seem off-putting to some. On first pass, it may sound like I am advocating poetic free-for-all, granting permission to anyone and everyone to simply spill their guts on the page, gifting the ravenous self a rigor-less carte-blanche and the right to claim absolute personal poetic prerogative.

Not at all! As EXHIBIT A, I present, in defense of personal rigor, the picture of Mary Meriam walking very deliberately up and down a flight of stairs, listening to how her breath rises and falls into the rhythms of iambic pentameter, drilling that natural meter into her unconscious. This is the exercise I remember her recommending to a poet on Eratosphere who seemed to be having trouble locating the meter in language. Arduous discovery is thus integral to personal poetic authority, for only that which one labors to uncover oneself can grant one the confidence needed for self-expression.

I am not rejecting poetic history wholesale. I am neither judging the poetic works of the past by modern standards which would have been incomprehensible to long-dead writers, nor making excuses for their admitted blind-spots. Each age has its own work to do, and part of the work of each subsequent age is the adjustment of both their backward- and forward-looking lenses. And though my sympathies may lie at times with the long-forgotten, those chewed-up and spit-out beyond the borders of poetic history, I can still appreciate the accomplishments of those center-stage.

But what I am advocating here is an entirely personal engagement with those past landmarks, be it positive or negative; one that involves an idiosyncratic intimacy with them, rather than a mechanical embrace; an intimacy that questions, rather than obeys; one that thus understands the deep necessity of both assent and dissent.

Mary and I recognized each other as kindred outsider souls, many years ago, in the then-vital poetic stomping grounds of Eratosphere’s online poetry workshops. The place was full of outspoken personalities then, delivering manifestos of the moment, donning various vanishing mantles of authority, which many of us delighted in poking full of holes. The sparks thus generated cast a lot of light into a lot of dark poetic corners. Almost all of us were united in our fascination with the tools of formalism—meter, rhyme, etc—and so there was an academy of sorts, but an academy of one’s peers, one that could be both listened to and resisted. Oh, I can’t tell you how many times, over the years, on behalf of both myself and other poets, I could not hold my tongue—and answered inane questions like Why is the tree blue? or How can a one-legged man run? or How can a table’s legs long for the floor? with this simple and curt reply: “Because the poet has said so.”

After participating in all the indisputable intricacies of metrical argument, I couldn’t believe that such a basic tenet of the poet’s authority could be so violated. We were not amateur scribblers, after all—the poetry board’s regulars took great pains to point that out (often to the point of self-congratulatory nausea). And so how could we then overlook the fundamental courtesy of allowing poets to make up their own minds about the directions they wanted to launch off into, outlandish though they may have seemed to some. Even now, after all these years, when I stand up on the Sphere for this personal poetic authority, I am often misunderstood, accused of acceding to any poetic hack’s trivial flights of fancy. Granted, such rash single-winged flying exercises are no doubt legion. But I am quite sure I know the difference between rank self-indulgence and unorthodox techniques of aerial navigation.

The bottom line is that when I am reading a poet I respect, the first thing I do is surrender to them control of the ship we travel on, allowing them to make their choices as they see fit, accepting the world they present it to me—grateful, in fact, to be somewhere other than in my own familiar realm. I give the same latitude to them as I give to Shakespeare or Frost, and am well aware that the awesome anomaly that people discuss ad infinitum in the work of the deceased latter may well be the fatal flaw they object to in the work of the living former. For just as there is something called dream logic, which often breaks the rules of workaday life, so there is something akin called poetic logic, and I have no doubt that it differs for every poet, perhaps even for every poem.

It has been such a joy over the years to watch Mary doing all those things which she shouldn’t be able to get away with. And not simply out of the exhilaration of storming the academic gates, but because the poems in which she does them demand it of her. And those odd tics and infelicities which I found a little uncomfortable in her early work—? How faithfully she has embraced them rather than rejected them, making them more hers, until she has turned them into skillful strokes of very personal genius. The occasional archaisms, the anthropomorphism, the devilishly persistent repetitions, the bold neologisms, the metrical substitutions, then suddenly the lack of metrical substitutions, the full-rhyme and the slant-rhyme and the no-rhyme, the quiet loss of punctuation—each a forbidden gesture that might annoy someone—all set like errant gems in her perfect up-and-down-the-stairs grasp of innate meter. I mean, listen to this:

“Where I Wait” I wait in honeysuckle thunder, the sharp alarming cries of crows. A storm approaching never blows my long undone undoing under. I hear sweet distant mourning doves, nearby woodpecker’s rhythmic tap. Suddenly leaves stand still in sap, hot sun, and sound. I wait for Love’s hand on my shoulder, “Hey lost one, stuck-in-the-woods, you bird-girl-leaf, who sings in springs without belief, don't trash your dope. I am not done.” At that, the breeze returns and lifts a forest-full of greeny gifts.

I must confess that I find it difficult to proceed straight through any of Mary’s books—difficult because after reading one poem I almost always close the book and just sit there, jaw-dropped. “How does she do it?” I find myself asking. And then I answer my own question: she does it by trusting her voice, her own voice, a voice which is unlike any other voice. Really, if Mary has had valuable teachers, those poets of the then and of the now are more-than-equaled by the ever-present Nature in which she has made her nest—by “the fat raccoon descending frontwards down the dying oak”, by “the loon that makes a V-mark in the mirror-lake”, by “the fattened leaves in summer’s breeze”, by “the sobs of herons”, “the bee’s rage”, and “the dictionary of owl”.

She makes much of her solitude in her poetry, often bemoaning it in extravagant fashion, but the fact remains that a poet’s vocation is arguably the most solitary of all artists. Poets need not perform, or collaborate—and unlike painters or musicians, the tools of their trade are simple and inexpensive, just a modest pen and paper will do, and these commodities remain available even to the poorest of souls. And so I come to EXHIBIT B: Mary Meriam, poor poet, alone in the forest, on permanent writer’s retreat. Having fled the noise and chaos of urban life decades ago, and settled with a similarly-minded soul in a lakeside house in the woods, but without a lover, the seemingly unstoppable momentum of her poverty and her solitude often came to seem like a burden—but if it was something that needed to be carried, the invisible muscle thus strengthened by the long forbearance of that load reveals itself more and more clearly in her poetry.

“Prayer For Leaf” The last old leaves have blown away, and I’m alone, undressed, and lost, shivering in a new spring breeze beside the lake that laps the shore. Blossom me slowly, bloom me good, and draw my fancy flowers nigh. Maple me softly, oak me strong, and let my close-green clothing grow.

The unburdening is palpable here, as poet becomes almost synonymous with leaf. The burden of loneliness that seemed to be a part of her very self, has grown weightless, has been stripped from her, has blown away with the last old leaves—and slowly, goodly, a new soft strength has bequeathed a more ethereal green garment. So—the self evolves—its suffering absorbed by nature. And the poet who emerges from this quiet drama can now write with supreme confidence: “I told the world the story of / My complicated love.”

Identity is a thorny issue for me, especially in the realm of poetry. And though, for Mary, it seems initially more straightforward—standing up for the excluded female voice, restoring sound to the silent semaphore of lesbian poets of ages past, and creating a forum, Lavender Review, for lesbian voices of the present—the notion of one’s identity, of one’s self, undergoes many transformations for a deeply engaged poet. For me, finding the self and losing the self are twin poles of the poet’s journey, and Mary seems to me ultimately to have done both: asserting herself in the public forum, losing herself in the forest.

It seems counter-intuitive to argue for the loss of self to any marginalized individual, to any one of the millions who have experienced not the loss, but the theft, of self. Faced with such theft, it is necessary for that self to stand up courageously and be counted. On a certain level, the endlessly echoed pop music aphorism that “learning to love your self is the greatest love of all” is a fundamental truth.

Yet even the most fundamental of truths can prove alarmingly double-edged, and the stronger one’s sense of self becomes, the more relative identity may come to seem—until the undeniable beauty of this self-resurgent, this self-triumphant, runs the risk that the victorious have always encountered, the inflation of self. In truth, it is this inflation of the self that the world has been suffering from for centuries. The white-male-self has built so many walls that all other selves have remained invisible behind them. But as these walls crumble, and as the dismantling of disenfranchisement proceeds, it is important not to replace one opaque wall with another.

For me, the sanity of selfhood lies in its transparency. Self should not be something that stops the eye, but rather something that one sees through—both literally, making visible what lies beyond it, like a window—and figuratively, employing it as a tool for vision, seeing by means of it, as through a pair of spectacles.

On a recent zoom call, discussing (among many other things) rudimentary plans for a reading,

Mary wanted to show me the gray hairs on her chin, hairs which she’d decided to let grow—

wondering if I thought they were too weird for the often-conservative general public.

“Who cares,” I said. “I like them, but I guess I’m weird.” “All of us are weird,” she chimed in. And, half-jokingly, I suggested that since we were all so weird, we should go whole-hog and perform the reading in drag. As has often happened in the past, Mary took my off-the-cuff suggestion and ran through the goal post with it. Before I knew it, she’d sent out an email to prospective readers, asking whether they’d like to participate in our Drag Zoom Poetry Event.

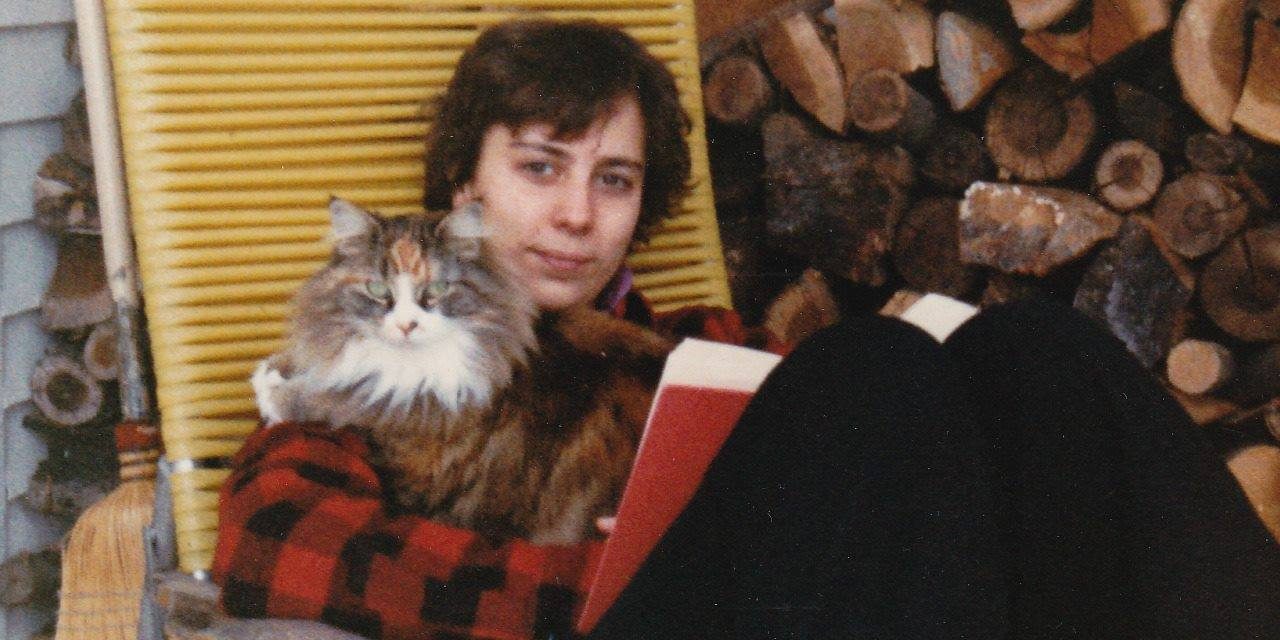

I must admit I had some second thoughts, anxious that the potentially rambunctious drag elements might get in the way of the seriousness of this little opening essay of mine, an essay I had been thinking about writing for a very long time. But as I riff on identity and the trans-parency of the self, the idea of playing with gender stereotypes during the event now seems quite apt. And so I offer my final exhibit, EXHIBIT C, a close-up of Mary Meriam’s gray chin hairs. Drag, it turns out, can be as simple as that—a gesture as slight as a few human hairs.

When I was a new-sprung gay youth in San Francisco in the late 1970’s, I hit upon drag as a way to wrench myself out of my shell. Granted, drag then, and drag now, are two different animals, transgression having become a short-cut to televised celebrity. And the understandably sensitive politics of transgenderism has complicated what seemed an innocent rebellion to my twenty-something self. But think of it like this: we are simply stepping outside our comfort zones here, offering our selves up as shifting palettes, willingly surrendering our dominant identities.

Mary has a poem, in Pools Of June, entitled “Trans*”—a poem that has always struck me as defiantly and wide-openly hermetic, a kind of cryptic hymn to liminality, to the moment of passage from one side to the other. I don’t even know if it is one of her more successful poems—at least not in the way that success is usually defined in literary terms. In fact, I have resisted trying to clarify its more baffling elements, if only because their very inexplicability seems indicative of the mystery of all trans-identities. The poem’s depths will not be plumbed. Its riddles may have answers, but I am not compelled to fathom them. And that fathomlessness, for me, is a cause—not for insecurity—but for celebration. And that fathomlessness is, as well, the essence of the poem.

“Trans*” Drown me now, sailor. Fir fir fir fir, o little white blossom, save me. She misses her mother, had a few surgeries. Now these wings on my back and a mustache. Now she’s telling me her dreams and nightmares. Just get off my back, this is my map. Sleepy, erudite, easy, ooooo, bat legs, foxy. No way will I have a birded head. Then she starts blooming into a striped wallflower. No one could look at the brown blind little creature. Take this red road to Rahway. You will find the sticks. The sticks will be bats. Toss them into the sea.

It seems a fittingly eccentric way to close out my song of appreciation to the True Countess of the Enchanted Forest Of Flatbroke, hairy-chinned Mary Meriam in her gorgeous gown of green leaves.

About R. Nemo Hill

R. Nemo Hill is the author of a novel, Pilgrim's Feather, and four books of poetry, The Strange Music of Erik Zann , When Men Bow Down, In No Man's Ear, and Magellan's Reveries. The editor and publisher of EXOT BOOKS, he lives in the Catskill Mountains of New York with his husband, where they make a subsistence living as indigo dyers.