Settlement: Bich Minh Nguyen’s Pioneer Girl

Pioneer Girl

by Bich Minh Nguyen

$26.95, Hardcover

Viking, 2014

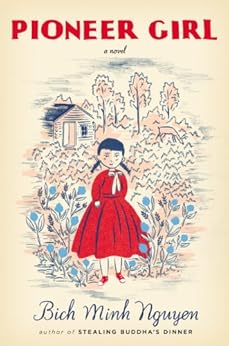

It’s no accident that the hardcover design of Bich Minh Nguyen’s Pioneer Girl evokes Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House On The Prairie books. The font is large like a children’s book; the dust-jacket made of slightly sepia-tinted stock; in the background, a log cabin with an open door, surrounded by meadow and flowers, with a grazing deer; in the foreground a little pioneer girl in pigtails. Except it isn’t a young Laura Ingalls. This little girl, wearing her Chucks with an old-fashioned red dress and bow, represents a more contemporary pioneer.

In pa’s restlessness, ma’s acquiescence; in settling and re-settling as they tried to find a comfortable and provident home; in the hardships the family faced as so many attempts met with disappointment; in the moments of success, cohesiveness, and relative comfort, when the family were able to rest and enjoy being part of a community; in the moments of affection and support that the family gave to one another: Little House presents a kind of extended metaphor for the experience of Nguyen’s own family. “[T]he Ingalls are pioneers in the mid-to-late 1800s moving westward, searching for a new home,” Nguyen explains in a recent NPR interview, “And my own family had come from Vietnam in 1975. And our experience as immigrants…moving to the West and searching for a new home, was parallel to the Ingalls’ experience as pioneers.”

A provocative mix of fiction and biography, Nguyen’s novel contains a complex plot that weaves together historical details about Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter/co-author Rose with the fictional lives of protagonist Lee Lien and her family. PhD in hand, unemployed, Lee has resigned herself to living with her mother and grandfather, working in the family cafe, while she looks for that ever-elusive faculty position. Returning to her family inevitably resumes unresolved conflict: Lee’s black-sheep brother chafes against their mother’s demands while Lee struggles to assert herself as an individual and as an embodiment of new cultural, class, and gender expectations.

When Lee rediscovers a gold pin depicting a little house by a pond, she learns that it was left behind in her grandfather’s cafe in Saigon, by a journalist known only as Rose who wrote about Vietnamese culture in the 1960s. Lee realizes (or decides) that the pin must have been the same as one mentioned in the Little House books, and that the mysterious Rose must have been Laura Ingalls Wilder’s daughter—thus drawing a literal connection between two “pioneer”families, separated by time and culture, who share similar challenges in establishing themselves in a midwestern landscape that is by degrees indifferent to hostile.

Lee sees Rose’s pin as an emblem of resolution to all the loose ends in her life, and feels compelled to track the pin to its source. She invests all her pent-up intellectual energy and unexpressed emotions about family, ambition, and personal identity into a search for the “truth” about Rose and Laura. It’s a quest to impose narrative coherence on people and events who are, ultimately, un-pin-down-able (yes, that was on purpose). Nguyen self-consciously draws on her own background in literary studies in her portrait of Lee as a scholar who has been trained in the instability of meaning, but who feels driven to look for it anyway.

In the course of Lee’s research, it comes to light that Laura and Rose had a tense relationship, full of conflict, dependence, and defiance. Rose was not content to live what she saw as the precarious yet mundane existence as a farmer’s wife that was laid out for her. At the first opportunity, she embarked on what would be an extremely unconventional life. She married, divorced, and then became a journalist who traveled the world on her own in search of a good story. Eventually, Rose became the co-author and editor of her mother’s Little House books. Lee feels a special connection with the Wilder women—the strength, stubbornness, and persistence of Laura and Rose are the same as those of Lee and her mother, yet the demands and constraints of the women’s situations make each generation nearly incomprehensible to the other.

The juxtaposition of such apparently disparate family narratives is fascinating. But Nguyen falters in some of the more workaday aspects of the writing. Her descriptions of setting, at once overly-conscientious and accurate, tend to fall flat. For example, Nguyen describes a certain type of Asian-American home on two levels. It works as nostalgia for those who recognize it with a mix of fondness and exasperation, and as a corrective for those who might only have had glimpses of it from the dining room of a cafe. But the result of her portrait is to make the subject seem more distant. Her description is more the examination of an artifact than an invitation to create emotional or imaginative connections. Her handling of Lee’s postgrad malaise reveals similar problems:

I’d been ready to poke fun at the MFA world Alex had immersed himself in… [but] I didn’t want the talk to turn to my own prospects. How I would have to force myself to revise my diss and turn it into articles; how I would have to try to get those articles published and do presentations at conferences. I would try to make the whole thing a book, or a monograph, as people in academe irritatingly called it; I would hit the job market again and try, try, try to land any kind of tenure-track assistant professorship or visiting assistant professorship…

I can relate—I’ve had that experience myself. However, as clearly as Nguyen explains Lee’s predicament, a reader unfamiliar with the lot of the humanities post-doc would struggle to pick up on the uncertainty, instability, frustration, and self-reproach characteristic of that condition. Nguyen’s development of the plot and themes is admirable, but her prose style sounds journalistically non-fictional—characteristic of a well-written blog or memoir. Of course, the novel is meant to be a fictional memoir (like the Little House books themselves), a set of significant episodes in Lee’s life. Yet, as a novelist, Nguyen doesn’t seem to have the elegance or depth needed to craft this into a truly engaging work of fiction, even one that mimics the prose of a memoir. Her skills either don’t fit the genre, or the framing device doesn’t serve them.

Still Pioneer Girl is a readable, engaging story—or mixture of stories—and it inspired me to pick up the Little House books. Having grown up Canadian, my youth was all about Anne of Green Gables; Little House on the Prairie was strictly a TV show. I wanted to experience the original texts, with their blend of fiction and (ghost-written) autobiography, combining honest recollections with self-revision (Laura) and self-promotion (Rose, who had the eye for the marketable). Although Nguyen emphasizes the pioneer/immigrant story as well as the mother/daughter conflicts in her novel, the real significance lies in her depiction of her narrator. Lee throws herself into an examination of the past, convinced that she will find a pattern, connections that will provide an explanatory model for her present experience:

Maybe it’s my chronic, lifetime second-generation problem. Looking forward and looking back, trying to locate the just-right-space in between. Always translating, and often getting the words wrong. Trying to figure out the clearest line of narrative, only to find more knots, more clouds. So far I have spent almost half of my life studying and thinking about American literature, and the landscape has seemed one of incredible, enduring, relentless longing. Everyone is always leaving each other, chasing down the next seeming opportunity…Where does it stop? Does it ever? I want to believe it all leads to something gander than the imagination, grander than the end-stop of the Pacific.

In the experiences of the restless women who’ve come before her, Lee hopes to find a template for settling all conflicts—with her culture, her mother, her professional choices, herself. Instead, the only way she can calm her own restlessness is to accept it, to accept the conflicts, to accept that, like the women who have come before her, she’s a pioneer, unable and unwilling to settle down, or to settle.

About Carol-Ann Farkas

Carol-Ann Farkas is a college professor and writer, with interests in 19th century fiction, medical history, wellness in popular culture, and the personal essay. Her study of the discourses of contested illness in medical and popular culture is forthcoming this winter in the journal Trespassing. Her attempts to negotiate human relationships are documented at ProfsProgressBlog.