It Puzzles the Will: Hamlet and Suicide

Madeline Levine, the celebrated author of Teach Your Children Well, recently gave a talk to the faculty of three loosely aligned independent schools, including my own.

She said a lot of sensible things—about focusing on positives rather than remediating fault, about allowing students to meander or even fail, about teaching them how to negotiate the dozens of tiny shocks that attempt to derail every day. She talked about how we as teachers (and parents) need to model our own efforts to stay out of the tailspin happening just over our left shoulder.

Like I said, a lot of sensible things. But here are the only specifics that stayed with me.

The kid makes the school not the other way around, she said. It maybe true, but as an educator in a room full of educators, it also made me feel like an outcast hedgehog in a room full of other outcast hedgehogs. And then there was this: the suicide rates among 10 to 14 year-olds are up 73% in the last five years. Mainly girls.

73% increase. A graphic number. As Levine put it: girls attempt more, boys complete more. One of the school counselors tells us the next day that suicide is now, after accidents, the leading cause of death among high-school age teenagers. I have an 10-year-old daughter who, when I ask her, says she knows the word “suicide,” but she’s not exactly sure what it means—something about hurting yourself, right?

The 73% statistic is even more disturbing because I’m supposed to lead a discussion of Hamlet’s “To Be Or Not To Be” speech to a group of high-school sophomores the following week. The play’s cultural centerpiece, the one example of English literary history most sophomores are actually familiar with, is a speech that ardently, falteringly, talks about the entering of the sleep of death as maybe the only heroic act—an act that defies the one true uncertainty. An act that, in fact, looks into the abyss of that uncertainty and steps into instead of away from.

How can I teach this to high-school sophomores as ever-increasing numbers of them are choosing not to bear the whips and scorns of time? Except carefully—a pitchfork without the prongs.

One way is to tell them that he’s not being literal, that he’s talking about an emotional “suicide,” and not, actually, about running a bare bodkin into that soft spot between the third and fourth ribs. However, to tackle the speech head-on, to deal with real daggers not just metaphoric ones, I begin light, deflect the sting a bit. I ask them about what, exactly, must give us pause? What’s the rub he’s on about? Can they list the five specific whips and scorns of time etc. I mix them up so those kids who sit next to each other in the front row, sit so straight they could balance uncooked eggs on their head, aren’t working together as the “what” and the “where” begin to sink in, and they begin to ask if he’s really talking about the thing they think he’s talking about. Emphasize context. That these are not tiny shocks, but the extenuating circumstances of a father murdered and a mother “whored.” Hamlet’s soul bereft, barefoot and haggard, barely intact, cut inside and out by his father’s murder, his mother’s remarrying, the throne mysteriously not passing to him, the break up with Ophelia, the constant attentions of her cuckoo clock father, his best friend Horatio being about as much fun as dried and hung out kippers.

This a response to all those shocks, an existential wrapping of them around him—not, as Madeline Levine puts it, a completion. Not even an attempt, but, rather, a mulling of its philosophical content.

A student asks about the lines about how conscience doth make cowards of us all and sicklies over the native hue of resolution with the pale cast of thought. This still about him killing himself, right? Not his uncle? Can it be both? So was Shakespeare depressed, somebody else asks. Not Shakespeare, I say, Hamlet. And he’s just talking. Unpacking, like a whore, his heart with words. Remember what he’s gone through. This part of what makes him remarkable: the ability to face pain, confront it, give it a geometric shape, even as, shape by shape, it consumes him.

Their faces are blank and untidy. Maybe Macbeth would have been a better choice—blood and gore and ambition. Hoping the discussion lands in the right way, I’m careful not to finish the class there, but to get to the confrontation with Ophelia and the break up. The Kenneth Branagh movie is so graphic: Hamlet holding her by the hair, the kids seeing Rose from Titanic dragged around this colossal, empty room of mirrors and gold filigree, her screams echoing off the mirrors—a 15-year-old girl caught between duty to her father, to her king, and then to her forbidden love. How to manage such impossibilities?

The students recognize Hamlet and Ophelia as instruments of and for their parents’ will. Even when both of them—especially Ophelia, the students add—are in the act of utterly losing their minds, the adults around them interpret their words for them without any genuine attempt to hear the fear, the pain, behind them.

We spend quite a bit of time on why parents put so much on their kids. Or if Hamlet ever gets to be Hamlet. If Ophelia slips. The parents, especially Polonius, upset them the most. That Gertrude won’t let Hamlet go back to school, that King Hamlet just expects Hamlet the younger to avenge, avenge, avenge. Polonius spying on his son away in France, just because. And on and on—the inability of Hamlet, or Ophelia, Laertes etc. to be themselves as opposed to being the young people their parents wish them to be. Parents as spies, as manipulative, as barely above vicariously motivated bottom-feeders.

These fourteen and fifteen-year-olds understand Hamlet’s ultimate dilemma to be one of identity: taking on the mantle of Prince of Denmark and all that comes with it, including the aforementioned dismantling of his uncle’s mortal coil; or, remaining Hamlet—the deeply wrought, Hoboken philosopher who feels in ways that make princedom too simply bifurcated an option.

Here they find a part of themselves in the play: in the question of Hamlet as Hamlet, Ophelia as Ophelia, the question of how much of the self each one inhabits as themselves. For instance, Hamlet as himself or rather a self ripped from its core and replaced by Fortinbras—the very name an immovable, martial structure—a thing designed and incarnated by the father. Hamlet is forced into becoming King Hamlet’s son: a prince with a set of particular expectations mapped out, expectations that create the brooding thug capable of murdering his friends, of abandoning Ophelia, of screeching shrilly at his mother. But this not really Hamlet, this some intruder, some space alien impostor spinning plates inside of him.

For many teenagers, this is the prime question: what part of me is me? Maybe more bluntly: what part of me is not my parent’s me?

Hamlet the prince whose will is not his own, as Laertes tells Ophelia. Who may not, as unvalued persons do, Carve for himself. Not Hamlet, but Prince Hamlet. Hamlet deferred. For the students, the self is constantly deferred into the dreams of their elders, not just their parents but the institutions that surround them, and, as if to salt the wound, a self constantly splintered via social media. Instagram names pun on their legal names rather than represent them: “Sea cough” for “Seekoff, or “Less of Her” for “Lesser”—and the irony of that last one for a fifteen-year-old girl is almost too much.

The struggle for many of them is to find a central pole from which to negotiate the world, from which to reach out in order to take risks and, ironically, to mold that pole into something that speaks of them not for them.

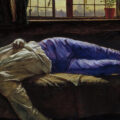

Ophelia is pushed to do the one thing Hamlet cannot find the courage for. Her act, to some of these students, seems not an act of escape, but the act of ultimate courage, a stepping away from the boundaries, the lives, ascribed to her so vehemently by the world outside of her. A bold step into a world where true uncertainty (and with it a true act of becoming) exists. Ophelia may be the only character in the play courageous enough to defy, in turn, the directives of all those who speak for her: her father, her brother, Hamlet, society, the church. Ophelia takes her teenage body into her own possession in the face of a society telling her she does not possess that ability, nor that right, though she possesses the right to allow herself to slip from a branch above a weeping brook. No wonder so many students see her as the play’s only truly heroic figure.

In a world denying her the self she aches for, Ophelia chooses to discard it. To make an analogy between the contemporary world and Elizabethan England may seem trite, but for so many young people either on the cusp of or in the midst of puberty, the world moves quickly in such complex ways that the self becomes increasingly difficult to locate, a self evolving and whirling around a center they cannot find.

Watching students in and out of the classroom as they struggle with this becomes ever more urgent as my own daughter begins the same struggle. Hamlet’s famous speech and Ophelia’s “completion” show at once the utter, tragic certainty of choosing the abyss while, ironically, providing a space to talk about alternatives. The alternative of Hamlet giving voice to his own internal anguish and through that quieting it. Perhaps more strikingly, the alternative of Shakespeare constructing a space where fear and pain become distilled into a set of resolutions, tragic as they are, enacted via the imagination. The imagination as the place possessing the depth and flexibility to absorb the constant psychic and emotional shocks that each day threaten to derail, the place where resolution becomes possible if we can learn to see ourselves not as two-dimensional receptors but as multi-dimensional makers.The place that keeps the world from spinning beyond reach, that keeps “Less of her,” from equating, ultimately, to “Lesser.”

About Giles Scott

Giles Scott has taught high school for 15 years, primarily in the Bay Area. His first book, a narrative non-fiction exploration of adoption and identity, The Anatomy of Longing, is forthcoming from Upset Press. Recent articles have appeared in The Washington Post, Catapult, and The Millions.