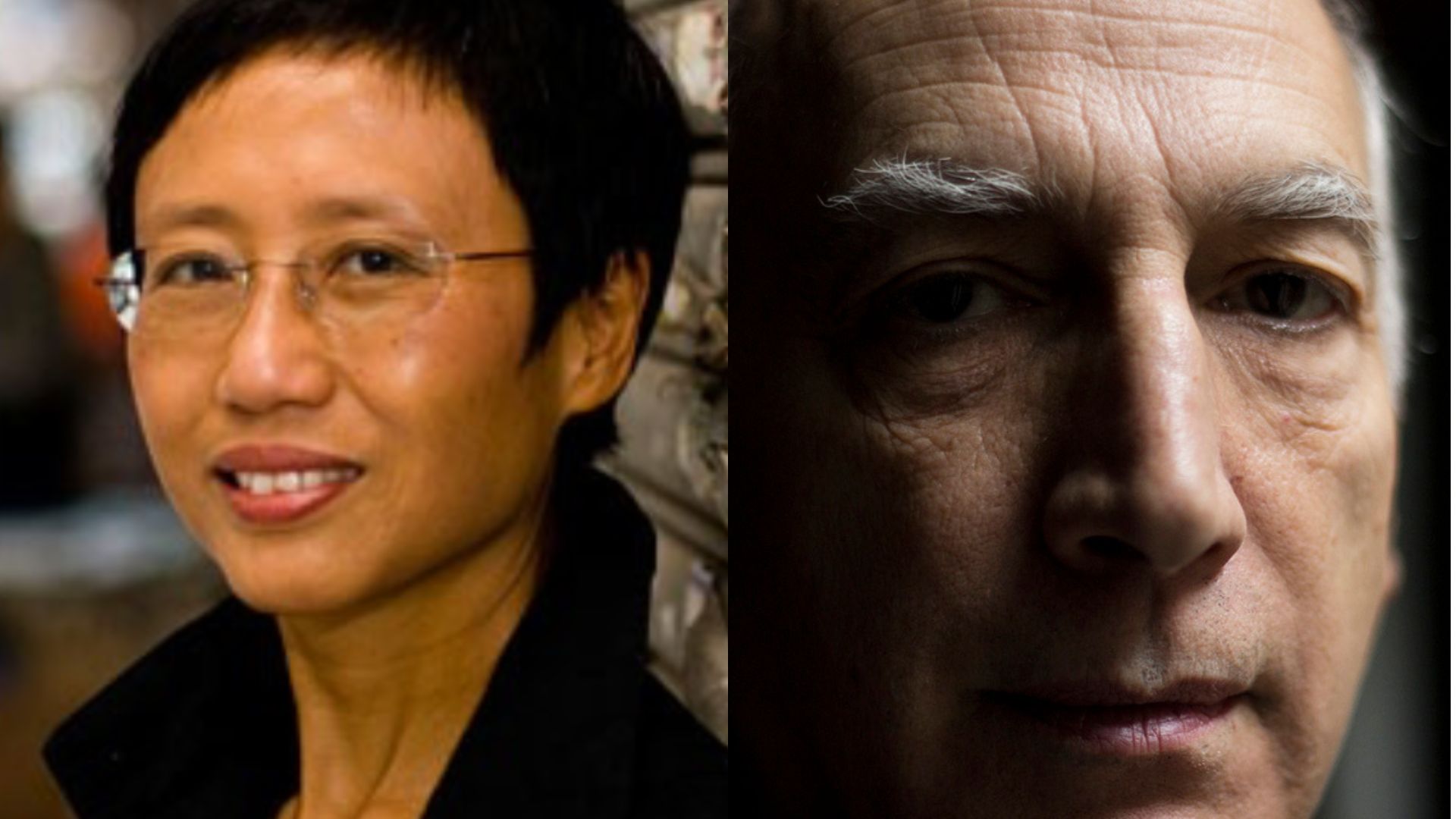

Conversations: Xu Xi and James Sherry

XU XI 許素細 has authored fifteen books, including the collections Monkey in Residence & Other Speculations (Nov 2022) and This Fish is Fowl: Essays of Being (2019) and the novel That Man in Our Lives (2016). She is co-founder of Authors at Large and is currently the William H.P. Jenks Chair in Contemporary Letters, College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts. A diehard transnational, she has long split her life between Hong Kong, New York, and the rest of the world. Follow her at @xuxiwriter on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

James Sherry is the author of 14 books of poetry and prose, most recently Selfie: Poetry, Social Change & Ecological Connection (Palgrave MacMillan, 2022) and the poetry book Entangled Bank (Chax Press, 2016). Since 1976, he has edited Roof Books and Roof Magazine, publishing nearly 200 titles of seminal works of language writing, flarf, conceptual poetry, new narrative, and environmental poetry. He started The Segue Foundation, Inc. in 1977, producing over 10,000 events of poetry and other arts in NYC.

Xu Xi: What most intrigued me about your book was the insistence on poetry and poetics as a force of change—in language, but also that it can create a connectivity across disciplines to find answers for the environmental and social issues of our day. That the construction of identity serves as a key leverage point to create change struck me as most curious and challenging. Why is the construction of identity so important to you as a poet, critic, and editor? In the chapter on “Borderlands” you make reference to the “narcissistic dysfunction among poets,” something you presumably have witnessed firsthand. Do you believe that the connections we make beyond our own groups and borders to “build social networks and flexible borderlands” can significantly change the environment for poetry?

James Sherry: Identity is important as a model for environmental thinking because culture and our way of thinking about ourselves has to change before some individuals will be willing to accept and act on climate change. Understanding the multiple conditions of identity, as opposed to assuming all culture relies on the unique individual, also helps us to see our surroundings as mutable. Individuals, societies, and ecosystems are singular, plural, and interconnected.

There are several levels at which identity is vital: “the poet” is not usually an objective narrator, but rather someone whose choice of words remains intimately engaged with their views of themselves as well as the themes that concern them. Selfie presents many examples of this complex relationship in addressing individual, social, and environmental problems of climate change.

I realized that about half the world is convinced of the facts of climate change, but the other half are prevented from accepting those facts because of cultural identities that make those facts difficult or even threatening to believe. For those people, culture must adapt to include not only their views of themselves, their families, and communities, but also their surroundings, how weather affects one’s ability and interest in accepting new ideas, how sunlight and rain temper a person’s beliefs, even how the density of life in one’s surroundings can determine the science they are willing to accept.

We must change culture to fight global warming. One important way to do that is through language. And what changes language more directly than poetry. I’m not claiming that reading a poem will change your attitude about global warming, but language frames the way we see ourselves and our interconnected world.

From the very start you also raise questions about any singular identity, writing: “We were not truly native but we were resident. We were not expatriate but our passports were foreign. We were not temporary but we were not permanent.”

How do you as the writer adjust to these many possible identities? How do multiple identity points of view play out for you in your mind as you undertake to write and then also in the writing process. Are all of these identities really distinguishable or do you integrate them in your overall curiosity and respect for your surroundings?

XX: The personal essay or memoir often embraces too many “I’s.” However, using 1st person plural is sort of cheating because a “we” presumes membership in a group whose permission I may or may not have acquired for the writing. After all, that’s what a writer does, presenting her opinion or perspective of a reality she lives. And the conventions in our language recognize that, so I think it’s possible to “get away with” this form of multiple identities.

I move between “I’s” and “You’s” and “We’s” until my editors say stop. It is impossible to remain stable in one identity when you write about memory. The “you” can be a little like that communal “we,”—almost like the royal we—that assumes an authority to say whatever it is the writer “I” is trying to say by claiming a certain authority to do so. It’s like this: the more I write about what I remember and wish to reflect on about my city and my life, the more I can somehow shape that point of view , which is a facet of identity. If that identity shifts or evolves , that is usually a result of either new information or new developments in either the city or my life. I think that’s why I seem to limit the topics I choose to write about in nonfiction , because I have many identities—e.g.: a former Indonesian national, a Hong Kong permanent resident, an American citizen, a mixed-ethnicity Asian, a former British colonial subject, someone who’s done various jobs, a writer, a member of my rather vast extended Chinese-Indonesian or Indonesian-Chinese diasporic family—and many aspects of those identities are not subjects about which I have a lot to say.

When I want distinguishable identities, I write fiction and inhabit “characters” as unlike myself as possible. My current novel in progress is called The Milton Man which features a mixed-race (Anglo-Canadian & Singapore Chinese-Indian) American male who is tall, loves to fish and began life as a Milton scholar, which is about as different from myself or my own life as I can imagine.

Selfie is a volume of literary theory that wants to dismantle the divisions between academic disciplines as well as socio-cultural groups in order to face climate change. What I’m most curious about is whether or not you believe the most likely readership of your book, which I imagine (perhaps incorrectly) to be principally literature academics and poets, would in fact extend your ideas across disciplines? Will it reach the social sciences and sciences into cross-disciplinary fora, whether in the classroom or in other academic or socio-political projects? Put another way, who do you think would be the most responsive readers of this book who may be persuaded to act on what you propose?

JS: The divisions between groups and disciplines don’t need to be dismantled. Organisms, social groups, and frames of thought have borders, and it’s these complex borders that need to be explored. The divisions are not one-dimensional property lines but rather broad areas of interaction. These borderlands are composed of countless but distinct connectors that need to be identified in order to understand what is within the thing, what is between things, and what operates across multiple things.

Selfie is being published by the culture division of Palgrave Macmillan. The anthropologist Amina Tawasil thinks it’s an anthropology book; the poet Rae Armantrout thinks it’s a poetry book. Its multidisciplinary approach has led it to be rejected by close friends who look after academic literary presses, saying cross-disciplinary work doesn’t sell. This situation makes me think of Selfie as poetry, liminal language, difficult to classify but distinct in its prosody. Nobody said that changing people’s minds would be easy.

What differences do you see between “immigrant writing,” such as that of Amy Tan and Maxine Hong Kingston, and your own “transnational” writing. Do you resist being part of one group or the other? Where do you see the connections or distinctions between these modes of writing as it relates to issues like craft, narrative, privilege, and your core themes?

XX: I’m definitely not an underprivileged immigrant who fled political repression or poverty to a better life in the U.S. Having lived a transnational life, it is a kind of privilege that allows me to ignore that classic Western Fitchean curve of storytelling that characterizes many immigrant stories. I didn’t go from the “rags” of autocracy or poverty to the “riches” of democracy and the opportunities of capitalism. Hong Kong is the most capitalist city in the world and my father was a beneficiary when I was a child, but he was also a victim who went bankrupt, which is easy to do in the capitalist system. My privilege was to have plenty to write about without resorting to only my immigration.

Likewise, I never had to search for cultural roots as detailed in many immigrant narratives because I grew up in a place where I looked like everyone else. The Asian-American story of going back to the “homeland” and finding you don’t belong is simply not my reality. However, I was still a minority in Hong Kong, and certainly in the US, although perhaps not as deracinated as many Asian-Americans who often strike me as “typically” American (to echo Gish Jen). I grew up bilingual Cantonese/English and China was not some mysterious, distant land. If anything, it was that irritating country next door you had to pay attention to and that I knew I “belonged” to but was myself “trapped” in a British colony, so my confusion was linked to being a colonial subject in a place which was populated mostly by Chinese who had fled communism. A tad confusing, no?

A colonial upbringing is both privileged and deracinating; English should not be my native tongue but it is, but not the way it is for an Asian American who grew up in a US suburb and had no other real choice but to be American and speak English to fit in and survive. You can live in Hong Kong and never speak or read a word of English, because by the 1970’s, Cantonese also became an official language alongside English. My upbringing was cosmopolitan and I continue to live a cosmopolitan life that was never fully rooted in just one place. America doesn’t dominate my consciousness the way it does in a lot of immigrant narratives, although my desire as a child to go to America was fueled by a marked preference for what American music and popular culture promised vs. the pageantry of the British Royal Family (I hated paying taxes to support them, which you do in Hong Kong, and I’m definitely not a royalist, even though I did binge-watch The Queen). I have sung and stood for three national anthems. But I don’t have to impress America or succeed American style to be the writer I want to be, whereas I believe many immigrant narratives are about “making it” in literary America. That’s sometimes a bit too much like Horatio Alger for comfort.

My literary career began outside America, which may be a less lucrative or fame-making literary space, but it did free me from the narrative most preferred by mainstream American publishing. The truth of the matter is that I didn’t live an immigrant’s life and as a result, the immigrant’s story is simply not what I need to write about. Nonetheless, Maxine Hong Kingston was a huge influence when I was in my 20’s because she was one of the few writers I read who looked like me but wrote in English, which gave me “permission” to embrace the English language as my own, despite the contradiction that meant for a part-Chinese writer writing about life in Hong Kong which was at the time, almost 98% Chinese. It didn’t bother me (as it does some Asian literary critics and readers) that Kingston’s Cantonese was only “baby Cantonese” since my Indonesian was the same. Criticizing or making fun of someone for being who they are is where racism begins, and I grew up with a lot of that in Hong Kong. Asian American literature has evolved quite significantly since Kingston, as has immigrant literature. It’s refreshing to read immigrant novels with characters who desire to “go back” to where they came from (or didn’t come from) because the American landscape is not where you can “be all you can be.” But that’s because Asians now comprise closer to 7% of the US population, not including Middle Easterners or Pacific Islanders, Inuit & Native Americans, and their stories matter a whole lot more.

JS: Rhododendron seems to emphasize people’s disbelief in humanity as a single entity. How do you think the frequent reiteration of racial identities and cultures affects your interest in cross-genre writing?

XX: A long time ago, I was contracted by a diversity consultant as a freelance researcher and case study writer to produce material about Asians in the American workplace. It was a short-term gig but memorable because my research into the US Census reports blew my mind. In 1980, Asians comprised 1.97% of the US population—and that classification “Asian” included Pacific Islanders, Inuit/Native Americans and Middle Easterners (very Ripley’s). In a memoir-novel I was writing at the time (although back then I called it a novel, a manuscript my agent declined to represent for which I am eternally grateful as it really was autofiction or a memoir-novel but I hadn’t fully worked out the true possibilities of those forms), I included this sentiment: when you’re less than 1% of the 2%, who gives a fuck about you or your story (I no longer recall the actual line but that was the emotional truth).

I also realized, as this was during my green-card days, that this country I was going to eventually pledge allegiance to had a pretty screwy view of humanity. This was shortly after I’d completed my MFA and my experience was how America’s literary view of humanity was the antithesis of “universal,” even though universality was the buzz word for how to write fiction well. There’s nothing universal about American suburbia—which is where most American fiction still takes place—until the rest of the world lives like that. But the rest of the world doesn’t live like that because most countries just are not comparable to the U.S. China is more comparable now, because it’s geographically large enough to be similar (although its population density is unlike the U.S.), but also because its economy and markets grew astoundingly in the last 30 or so years and China is now a superpower. Modern China does look like and act like a sort of Bizarro version of America , which makes China a country that is a lot like America today when it comes to how one nation believes a culture “should” be.

What’s more interesting to me, however, is that there are 50+ ethnic groups (even though the population is 90% Han) in China, plus a plethora of languages/dialects, even if China likes to pretend Han culture and Mandarin are all that should matter. Very WASP-MAGA, don’t you think? Meanwhile, the overseas Chinese diaspora—generally known as the 華僑 hua qiao in Mandarin or wah kiu in Cantonese—are a significant factor in what is “Chinese” in the world. When I first started traveling, I always made a point of finding the Chinese restaurants or neighborhoods and talking to the people there. It was startling to me how many ways of being “Chinese” there were. In particular, this was true of much of Asia. My story “The Youngest Child” in this new collection imagines this diaspora as a large and unwieldy family of sibling-countries, all of who are doing their best to please Ma and Pa China on the mainland, but who have each become de-Sinocized or have redefined what being Chinese is in their respective countries. I think of them as trans-everything – trans-lingual, -cultural, -religious, even -gendered. A philosopher whose work has influenced quite a lot of my thinking in this regard is Kwame Anthony Appiah, who wrote, among other books Cosmopolitanism.

What does this have to do with cross-genre writing? Trying to write for so-called universal appeal, I could finally eschew the idea of universality entirely. It’s a myth taught in creative writing that I refuse to reprise. Instead, I look to the local, the real, with all its messy, unbox-able racial, cultural, linguistic, ethnic, religious confusions and say, that’s what we need to write. So the challenge is to find a form that will reflect that messy reality of the way the world actually is, instead of pretending that the English language literary tradition is universal, because it’s not. Often, by disregarding genre boundaries, we can find language to shape the content of the world as we each see it, including in the suburbs of Cincinnati or Chengdu.

I am intrigued by your idea that we as a species need to learn to accept “rangy behavior” if we are to survive. You call for the rebalancing of the “overweighted position of individualism.” Do you think that we are still in that overweighted position in literary culture ? Or are we beginning to see more of that “rangy behavior” in this much more polarized political, social and cultural environment?

JS: Our generation of baby boomers was particularly driven toward individualism. We were relentlessly pursued by consumer advertising, the value of career ambition, psychoanalysis, and even the counterculture to consider our own identity and needs as central to understanding the truth—and life itself.

In the 1970s climate scientists began to present models that showed how CO2 and methane emissions would warm the planet to the extent that we would lose the relatively benign ecosystems that support such immense populations of humans. In mathematics, complex systems describe a collective with a large number of interconnected elements. Mandelbrot’s fractals, work at the Santa Fe Institute, Robert Shaw’s group at Santa Cruz, and the entire idea of ecology as the relationships between things rather than the things themselves drive us to see things as complex.

While I agree that the cutting edge has already moved more toward understanding rangy solutions, I worry that global corporations and autocratic regimes hand-in-hand have too great a vested interest in singular solutions: buy my stuff, adhere to my politics, think like me. The movement toward rangy solutions is not new as you point out, but we have a long way to go to see self interest as a multiple and ranges of success as inevitable. Even the fact of our organisms apparently operating as a unit makes rangy solutions difficult to accept.

I was intrigued by your book’s end-note. The Chinese personal essay seems central to your form in this book. Can you talk about the Chinese literary basis of this book and the two types of Chinese essay?

XX: This is actually a very interesting question because I don’t think I consciously reprise the Chinese essay. I am not formally educated in Chinese literature and my Chinese literacy is only about 60% (if I’m being generous, these days it’s probably closer to 40%), similar to my French literacy. I’ve never been a good student of languages because English(es), in my books, was sufficient language(s) to keep me writing, guessing and learning for life. Except for a period in the 80’s/early 90’s when I read some short stories and one novel by Eileen Chang (Zhang Ai-ling) in Chinese (The Golden Canque), as well as Sung & Tang dynasty poetry plus Lao Tzu and Confucius in Chinese (I succeeded for only one Confucian analect and one poem by Li Po), most of my reading of Chinese literature and philosophy has been in English translation. Likewise, of the essay forms you refer to, the only one I’m somewhat familiar with is the one that can be loosely translated as “miscellaneous literature or writings,” which appears in many Chinese newspapers. These are similar to the kinds of essays Montaigne wrote, but can also be like Swift’s writings or other English essayists of the early 20th century, or even op-eds AND very much like contemporary CNF forms. In that respect there is at least this one Chinese essay form that strikes me as very similar to what CNF essays look like today, an “everything goes” form – narrative, braided, lyric, flash, prose-poem, list, “hermit-crab,” speculative-fictional, autofictional, visual etc., etc. A lot like poetry, no?

I didn’t discover that Chinese essay form until the early 1990’s, the decade I lived and worked full time in Hong Kong and Asia. I had spent the previous 11 years living full-time in the U S, during which I became an American citizen. One of my Canadian aunts was a literary writer from Hong Kong who wrote essays for the Canadian edition of the major Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao (名報). She gave me her book of these essays about Canadian-Chinese life in Toronto, which I found an intriguing concept. I had been studying Mandarin for several years at that point. Since part of my marketing job (for Federal Express) also covered PR, I used to skim the major Chinese dailies each workday morning. During those years I befriended Lau Kin-wai, an art critic/writer, who wrote this same essay form about art, culture and life in Hong Kong, especially about food & sex (he was the curator who first exhibited the late “King of Kowloon” street artist, a kind of Hong Kong Banksy who graffitied nonsense characters in a unique script of his own all over the city. Later he also opened one of the first “home kitchen” restaurants in the city) as well as the late poet Ya Si (pen name)/Leung Ping-kwan, who was Hong Kong’s informal Cantonese poet-laureate and also wrote essays in that form. This did influence my own writing because that was when I first began to see the possibilities of the essay as a literary form. I often got commissioned to write op/eds and travel pieces for local and regional English language media. I suppose that’s the origin of anything that resembles the personal Chinese essay in this collection. In the early 2000s, I began adjunct teaching at low-residency MFA’s and met and read many CNF writers who were influential to my understanding of the genre—in particular Robin Hemley, Sue William Silverman and Patrick Madden, all notable American writers of CNF from whom I learned a great deal about the possibilities of form.

In your chapter on “How can culture change habitat?” you pose two compelling questions: Does the focus of poetry on self translate to high public value and public agency or does it reinforce consumerism? Do poets lose the ability to influence their societies and their surroundings as they deal with themselves?

The question I want to ask is about the enterprise that is poetry. Even as someone who does read some poetry and who was educated in literature, it still seems to me that poetry (and all that surrounds its production, publication, performance, publicity) only reaches a very small part of the general public, at least in the U.S. (this is not always the case elsewhere). Beyond the Amanda Gorman example of expressive poetics you cite, can the enterprise of poetry in this country have a large enough physical impact on habitat, specifically the habitat that is rapidly suffering degradation due to climate change?

JS: Selfie is less concerned with the ways poetry alone influences people to change how they think about their surroundings and more focused on how poetry interacts with other disciplines, ways of writing and thinking, and the social/environmental context that we all share. Selfie hopes to use poetry to demonstrate how connection works even in this most solitary of arts. Of course, poetry has some influence, but in this age of digital media focused on the visual, poetry remains weakly connected to mainstream culture. Oddly, poetry’s underground condition in popular culture frees it to be what it wants to be, rather than what the accountants want it to be.

But the ideas behind poetry are at best tentative and more often expose the weakness of solutions to the American experiment. Individuals in contemporary poetry are rarely heroic. Social interaction is celebrated as an alternative to institutional oppression. Nature is celebrated as an alternative to human degradation. Of course, neither of these is the case as poetry often shills for institutions and human degradation is oh so natural.

I don’t want to make a narrow argument for poetry’s specific effects because that is a kind of false consciousness. Rather I want to show in this chapter how poetry allied with other language methods supports events that change language and vice versa though channels that connect in both directions.

When I was first reading Monkey in Residence, I had the impression that I was sometimes reading fiction and sometimes reading memoir. How do you see the distinction between fiction and non-fiction, between fact and invention, between what you remember and how you remember it?

XX: I used to draw very clear lines between fiction and nonfiction, but that was before I began writing nonfiction as a literary, rather than journalistic, form.

Fiction was and still is for me all about invention. Even though the very real city of Hong Kong is often the backdrop of much of my fiction, it’s still a kind of fictional reality because it’s peopled with characters and stories I made up which never happened. But I am rather adamant about factual accuracy in terms of geographical and historical reality. The streets, train stations, even buildings I identify in Hong Kong and New York (the two cities that have appeared the most in my fiction) are all real. While I might make up what happens inside these buildings or transform them into something other than what they really are, a determined enough reader can actually locate all these places.

When I first began writing nonfiction, the pieces were usually commissioned by editors of newspapers and journals. They were mostly first-person accounts of my writing life & travels, some travel journalism or a modern Asian woman’s experience negotiating life in a man’s world. That kind of thing. I was always factual, and would never dream of making up something or even changing a timeline for a better story. Some of these I might never have written had it not been for the call from these editors. Others led to my interest in literary nonfiction. Once I started writing for myself, the genre reshaped itself in my mind.Today, the boundaries between fiction and nonfiction have begun to blur. While I still like to begin from fact, I also lean into speculative forms, especially for making political commentary. The “speculative nonfiction” piece in this new collection titled “A Brief History of Deficit, Disquiet & Disbelief by 飛 蚊 FeiMan” is the one I most enjoyed writing. It required a deep dive into the third book of Gulliver’s Travels, which is a classic example of speculative nonfiction – Swift presents Gulliver’s Travels as a “real” travelogue, though it is entirely fictional; the book is however a spectacular satire of many real political and social issues. I tried to do likewise, and mixed factual and speculative footnotes in the text – the factual ones draw from memory or deliberately distort real news into speculative news as a way to address a number of socio-political-historical issues of modern China and Hong Kong. Fiction and nonfiction have begun to blur anyway in publishing—autofiction has become rather popular, as has the “nonfiction novel.”