Conversations: Niloufar Talebi and Zack Rogow

The Critical Flame is thrilled to feature this conversation between author, award-winning translator, multidisciplinary artist, and producer Niloufar Talebi and author, editor, translator Zack Rogow. Special thanks are due to CF contributing editor Valerie Duff-Strautmann, who made this possible.

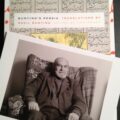

Niloufar Talebi is an author, award-winning translator, interdisciplinary artist, and producer. Her recent projects, both inspired by the Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlou, are the memoir Self-Portrait in Bloom (2019), called “a hybrid wonder” by The Rumpus, and Abraham in Flames, one of San Francisco Chronicle’s best classical and new music performances of 2019. Her TEDxBerkeley talk is “On Making Beauty After Agony.” Other projects include serving as editor/translator of Belonging: New Poetry by Iranians Around the World and its theatrical performance ICARUS/RISE, The Persian Rite of Spring (LA County Museum of Art), Fire Angels (Carnegie Hall, Cal Performances), The Plentiful Peach (Stanford Live), and Epiphany (BAM). Find more at www.niloufartalebi.com.

Zack Rogow’s ninth book of poems, Irreverent Litanies, was issued by Regal House Publishing. He is also writing a series of plays about authors. The most recent of these, Colette Uncensored, had its first staged reading at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC, and ran in London, San Francisco, and Portland. His blog, Advice for Writers, has more than 200 posts on topics of interest to writers. He serves as a contributing editor of Catamaran Literary Reader. Find more at www.zackrogow.com.

Zack Rogow: You’ve spent much of your literary life as a translator, conveying the work, stories, and memories of others. Your hybrid memoir, Self-Portrait in Bloom, contains a trove of your own memories and stories, including parts of your life that I’ve never heard you share before, even with friends. How were you able finally to open up and access those experiences in writing this book?

Niloufar Talebi: My relationship with text has always been full-spectrum: I translate, yes, and I also write, curate, remix, set, and use text as the springboard for multimedia works. A few years ago, it became crystal clear to me that the cardinal task of an artist, particularly of a writer, is TRUTH, so that readers could feel less forsaken, monstrous. I know I am delivered from pain when I read of other people’s trials. This knowledge liberated me to write of the ruptures in my own life, setbacks, betrayals, inexplicable enmities, but also profound gestures of goodwill and fortuitous alliances, and I’ve never looked back. This is not to be mistaken with flaunting self-indulgent secrets that are of no use to others, by the way!

ZR: This is an area where you and I have connected deeply—I also see text as not limited to the page, but expanding to a wider community of arts. I grew up in New York, steeped in the tradition of the Broadway musical and the American Songbook, where words and performance were in constant dialogue. I also see collaboration with artists who work in other media as huge opportunities for a text to reach other audiences.

To what extent is it vital for a creative artist to access and incorporate childhood experience and memories into her/his work?

NT: Memories are a moving target. They shapeshift with time, endlessly rewriting our narratives and hence identities. So it seems inevitable that we examine our past to keep understanding our world and discovering our own mysteries. In this way, childhood become an endless repository for mining stories.

ZR: The renowned Iranian writer Ahmad Shamlou (1925-2000) is a major presence in this book, almost more than the narrator herself. In describing him, you say, “He was a storyteller with the skills of an orator, enlisting his cutting wit, charm, masterful turns of phrase, and a vast syntax that went from low to high as he held court wherever he was.” I thought at first this might be a good description of you, and your own use of language. Did you learn how to combine various levels of diction in English from hearing Shamlou’s Persian? How does a writer combine colloquial street-smart diction with the features of high literary art, such as metaphor, rhyme, classical music, etc.?

NT: In many ways, Self-Portrait in Bloom deflects the “self” in the same vein as Gertrude Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. While Stein bent the form of autobiography by authoring one on behalf of the subject, I bent the form of memoir to generate biographical material on Shamlou and include a book-length selection of his poetry in my translation within the memoir. My book is a non-linear latticework that includes images, reflecting the mechanism of memory.

As to the possibility of language, if I am as acrobatic with language as Shamlou, then Eureka! Using various registers in English, interweaving current vernacular into classical, cross-disciplinary language, is my true voice. For years I thought “literary” had to do with high register, but I am also a person in the world in the now, so I channeled my actual voice.

ZR: It’s interesting that the mixing of colloquial and literary speech is also an important pathway in Iranian literature. That’s certainly something that provides tremendous inspiration for North American writers, in particular my literary mentor, the poet/librettist/essayist June Jordan. It was also huge influence for me in my book Talking with the Radio: poems inspired by jazz and popular music, where I tried to combine the stories and idioms of popular music with poetry, even formal poetry.

Could you talk more about Ahmad Shamlou and how he became a role model for you as the epitome of the creative artist? You paint him in the book in such loving and reverential terms, even as a sort of uncle. Did he also have qualities that you would not want to emulate?

NT: Shamlou has become part of my very DNA. He is a larger-than-life and ever-present muse. His influence has pervaded my life gradually and unconsciously, there never being a definitive moment of declaring him a “mentor.”

Writing a complex—and yet unknown to Western audiences—figure such as Shamlou was tricky. I wanted to properly convey the enormity of his status as a cultural figure to the West, but not to idealize him with a panegyric as so many do. The benefit of proximity to him meant seeing more than a faraway giant, which helped round out his representation, I hope. He had intuited how to “be” Shamlou, the giant everyone needed him to be, at once masculine, combative, unafraid, witty, sensitive, and poetic. As to qualities I might not want to emulate, I cannot be sure, but as I speculate in the chapter called “The Master and Margarita,” Shamlou’s relationship to women operated within a patriarchal framework, characteristic of his Zeitgeist perhaps. Whereas for me, in my time, national, and global circumstances, propelling stories of women is paramount.

ZR: You portray Shamlou as a highly political writer, but also as an artist who did not believe in social realism or the view of literature as propaganda for the masses. How does an artist remain political and relevant while still creating work that has complexity and depth?

NT: To navigate that fine line, what an achievement! In some of his work, Shamlou channeled and innovated with, rather than dismiss, the essential “lower” registers of language and folk culture. He preferred the company of working people. So while he worked at the other end of the literary spectrum as well, his work appealed to “the masses” because of his commitment to their plight, transmitted to them by social activists for whom Shamlou’s work was the language of resistance. Shamlou regarded his more political work to be extremely personal and vice versa.

His beliefs around that duality evolved with the discourses of his time—the mid-to-late twentieth century. Today, with the digital and information revolution and our consumption of late-stage capitalist agendas, endangering our very planet, the character of the “masses” has shifted, so who knows what Shamlou’s antidote for liberation would be today.

ZR: To me, the concept of “the masses” has gotten filtered through several prisms during the last several decades. The aims of the progressive movement, or the Left, have expanded to include more than just the traditional demand for economic equality. Increasingly, progressive goals require some education to understand and support: ecology, feminism, diversity, inclusion, world government over national self-interest. And education is often denied to working-class people. Siding with “the masses” is still vital for artists, but it has to be broadened now, in my view, to include everything from climate change, to reproductive freedom, to multiculturalism.

Could you share some of your thoughts on what you describe as Shamlou’s approach to translation, where he rephrased and even rewrote classics in order to make them come alive in Persian? Is that also your approach in translating into English?

NT: Shamlou worked with language intermediaries to translate dozens of authors and hundreds of works into Persian from many languages, including English, Spanish, Russian, French, German, Japanese, Spanish, Portuguese, Turkish, Armenian, Greek, Hungarian, and more. He took liberties with texts when he thought the translation needed it to flourish in the target language and culture. Shamlou was critical of translators who did not take that task seriously. He was not immune to making small errors in his process, but they pale in comparison to the contribution his massive body of translation work made to the Persian readership as well as to the cultural revolution he fomented from the aesthetic ideas he received through those texts.

ZR: You and I both see literary translation as a natural match for the performing arts. How did you personally arrive at that realization that those two disciplines, often seen as vastly different, could effectively be combined? Why do you see is “literary translation” as a natural match for the performing arts?

NT: Aside from being wired as a multidisciplinary artist, my purpose for creating performance projects based on the works I bridge over from Iran—the vilified country du jour—is to further their reach to new audiences. So for me, extra bridge-building is a matter of urgency and advocacy. You translate predominantly from the French, which is more visible as a whole in English. So what are your reasons?

ZR: I think the literary arts have become somewhat isolated in the arts world in North America and Western Europe, and poetry in particular. There are many art lovers and lovers of literature who would not pick up a book of poetry, contrary to the situation a hundred years ago, for instance, or the situation in many other parts of the world. For the literary arts to break out of that isolation, it’s important to recapture the connection between literature and the performing arts, a connection that existed very strongly in ancient Greece or medieval Provence, just to name a couple of historical periods in the West. That connection continues today in many parts of the world, from singing ghazals in Urdu, to pansori dramas in Korea.

In my own work, I’ve tried to wed literary translation and performance is works like Colette Uncensored, a one-woman show on the life and work of the French author Colette, developed with the performer and writer Lorri Holt.

NT: Not to mention Naghali, the practice of public storytelling in Iran.

ZR: How has your approach to combining performing arts and literary translation evolved over time?

NT: I dramatically narrated poems in two languages with musical, video, and dance artist collaborators in poetry-performances such as Midnight Approaches and ICARUS/RISE, dramatizing the poems in my first book, Belonging: New Poetry by Iranians Around the World (North Atlantic Books, 2008). Zack, you helped the structure of ICARUS/RISE as dramaturg.

I then expanded my translation approach in Love, Carnal and Divine, by scrambling lines of classical poetry to render metric and dramatic lines in English best suited for performance. I believe this is how Fitzgerald scrambled lines from Omar Khayyam’s Ruba’iyat in his translations.

Later, in The Persian Rite of Spring, a performance about Nowruz, I composed and performed a trilingual text from Persian poems, folksongs, ancient gathas, and my own writing to make their connections.

In my work with classical music composers I have written libretti inspired by Persian mythology and poetry, sung by operatic voices. My most recent work, Abraham in Flames (Z Space, 2019) with composer Aleksandra Vrebalov is the operatic companion to Self-Portrait in Bloom. I originally intended to compose a libretto of collaged lines from Shamlou’s poetry, but because of the act of silencing my project was met with—which I recount in Self-Portrait in Bloom—we side-stepped textual quotations by drawing on the powerful metaphors in Shamlou’s work to conceive the opera. The final work of art was more arresting than the original concept might have been.

I see all of these ways of engaging with texts and cultural material from Iran as acts of cultural translation.