Borderwork: Katarina Zdjelar’s Käthe Kollwitz

Hold my breath, then take in air, hands part-raised in a mini-lament, up on the balls of both feet. I do not want to suggest my gallery-going is all dance improv, but I have this project to register, record and dwell upon my encounters with the work of artist Käthe Kollwitz. It could be in a group exhibition in London, new and old monographs, online remains, the artist’s journals and letters, a play by Gerhart Hauptmann, or a poem-bio of her life by Muriel Rukeyser. To view the animated films of South African artist William Kentridge as if Kollwitz’s own charcoal drawings had come alive.

It accumulates, repeats, obsesses, this interest in Kollwitz’s work, always back to the physical shock of her art: that love, grief, suffering, protest of bodies drawn, carved, etched and sculpted, a physical contagion I am exposed to, until my body moves in a moment Kollwitz enables.

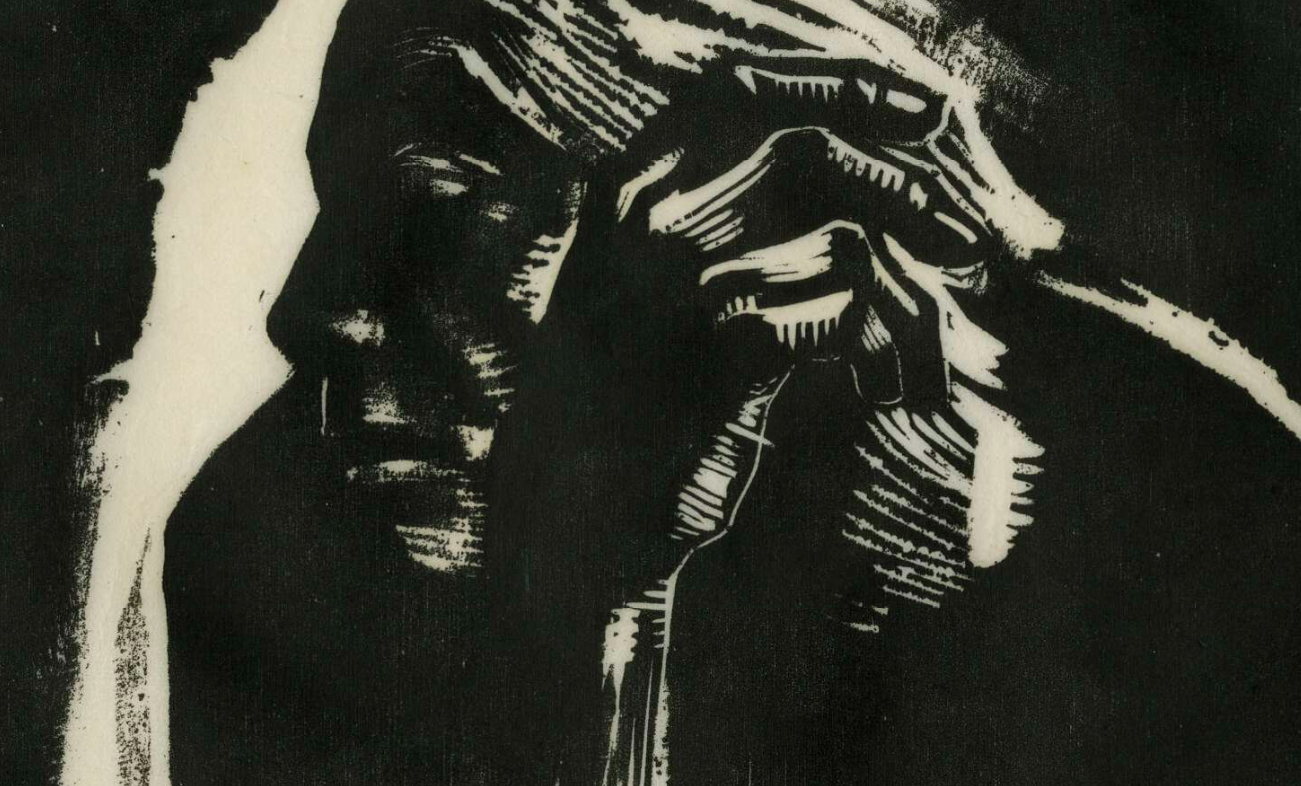

A small pamphlet by Katarina Zdjelar, an artist based in Belgrade and Rotterdam, begins with Kollwitz’s 1929 woodcut Mary and Elizabeth. Zdjelar states the basics of the image: “Two female bodies. Facing one another”. What we see often recurs in Kollwitz’s work, how: “the margins of one body dissolve? One body floods, bleeds, leaks, rivers into another… Bodies, their physicality, extends and morphs. As if bodies had openings. Attachable openings.”

In Mary and Elizabeth this is delicate: two separate figures, one laying a hand on the swollen pregnant belly of the other. But my immediate thought when I read of bodies dissolving is about drawings, prints, sculptures by Kollwitz where two bodies clasp. It might be a mother and child, the infant might be dead, or two lovers, or an emaciated woman clutched by a skeleton of Death.

The grasp is as intense and complete as a body can muster, but its power is limited. The child will not come back to life. No Ovid-like metamorphoses transforms these or any lovers.

Zdjelar’s pamphlet was written during Covid, to continue her investigations into the all-women’s dance studio founded by choreographer Dore Hoyer, in Dresden in 1945, which focussed on archival photographs of Hoyer’s 1946 performance Tanz für Käthe Kollwitz. These were shown by Zdjelar to performers, activists, and dancers, who were asked to freely respond. From online documentation of several different exhibitions by Zdjelar I made a composite of what I think happened:

On a screen suspended in the darkened gallery a film shows combinations of hands and arms come together, clasp, intertwine, rest, come apart. Sometimes the screen is empty until a hand enters the frame, soon another collective improvisation is underway amongst body parts whose gender, race, age, and class is made both multiple and undefined by the camera’s tight framing of the movement. Three smaller screens on floor and wall of the gallery each show one body: here a single arm comes, moves, exits on its own; another screen shows a woman with eyes closed resting her head on her finger tip. Finally, a young dancer poses, perhaps partly inhabiting the similarly enfolded and rounded forms of many grieving mothers in Kollwitz’s drawing and sculpture.

Behind the dancers a blurred but still radiant white and yellow is reproducing a pattern designed by women working at PAUSA, a German textile factory run by a Jewish family involved in anti-Nazi resistance. Panels on the floor and against walls are decorated with graphic marks which resemble isolated strokes and grooves off Kollwitz wood cuts. Juxtaposed with the screens on floor and wall are black and white prints showing blow-ups of details from the archival Hoyer photographs. The photos themselves are shown in display cases, where Zdjelar has made curving, snake-like strips of clear and coloured glass that are laid or fixed above the photographic prints. Is this an abstraction of the dancers’ moves? The beginnings of a new language? Broken neon ruins of other forms of spectacle? A line of original Kollwitz prints hang on the far wall.

Have I mis-read Zdjelar’s project in my online sampling, combining exhibitions across years and continents? With only fragments of video on the web, I cannot find the rhythm Zdjelar gave to her films, which the dancers found for their interactions and solitude. It is replaced by rhythms of web searches, promo films, a curator statement, press releases, the artist’s website. And a free, exploratory movement of hands and arms is rarely (never?) experienced in a Kollwitz print or drawing.

Zdjelar’s pamphlet does not cite all these prior incarnations, but writes its own moves afresh out of all that thought, moving, making. Of Hoyer, in Borderwork, Zdjelar notes how: “Her body was not the body of a choreographer. Nor of a dancer. But a medium for presence.” After a pause of white space on the page she adds: “Bodies running through her body. The body as a channel.”

Zdjelar attributes the same extended sense of body to Kollwitz, who could not distinguish her own body from those she depicted, turning to her own mirror image as much as those others she observed, sketched, remembered. This “solidarity” leads to the proposition that gives Zdjelar her title: “Bodies are borderlands” so “could Kollwitz’s practice be described as a practice of border work?” She references Gloria Anzaldúa when observing: “borderlands do indeed emerge when we edge each other with our gender, cultural, racial, class markers, when these differences touch, when the spaces between two individuals shrink with intimacy.”

But what is this “solidarity” that Zdjelar finds in the middle-class woman who melds her body into the working-class lives she depicts? Maybe the entangled hands in Zdjelar’s video suggest how to start with possibilities, limits, fragility, touch, mediation.

Zdjelar’s pamphlet is an intervention in my chronicling of Kollwitz encounters. In After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art at London’s National Gallery, a small bronze sculpture is in a glass case. Pair of Lovers (Liebsgruppe), 1913-15, reads the label. A young woman sits on the lap of a seated man, who holds in his hands her head into which he buries his face. Her arm hangs limply down. As Kollwitz might have used her own body as partial model for either figure, so I try to understand this sculpture through the “solidarity” of my own body: filling in when details of the figures are lost in a bronze mass, imagining what grief or affection puts me in such a position, or simply trying to weight in my mind a precise sense of their embrace: his hands on her head, the feel of that hanging arm.

Love, grief, death, surrender: if the label suggests a romantic couple the intensity also suggests a mother and her dead child.

I thought of Kollwitz prior to this, when I saw a William Kentridge retrospective at the Royal Academy on Piccadilly, in December 2022. There was a display of Kollwitz upstairs as part of the Making Modernism show, and the times I went to visit both exhibitions I had a fantasy of the two artists meeting on the RA staircase.

In 1980s Apartheid South Africa, I imagined Kollwitz asking Kentridge, why did he place so much emphasis on the landscape surrounding his charcoal figures, be it urban edge land, racially segregated beaches, drive-in cinemas, crumbling Colonial museums, Johannesburg streets, car interiors, or ballrooms? Why the urge to animation and its unfolding narrative, rather than discrete moments in a print series?

Kentridge shrugged, had a question of his own. Why, given a ferocity equal to George Grosz or Honoré Daumier, did Kollwitz never satirise, that energy of critique instead shaping the monumental backs of mothers, whose hunched shape was her own? Why the mechanical theaters? replied Kollwitz, and all those operas, film installations, concerts, when his charcoal drawings showed Kentridge saw how much a human body told, in itself, on its own.

When Zdjelar writes of grounding her work in the archive, she means both actual institutions, such as the Dance Museum Archives in Cologne where she finds the Hoyer photographs, and a more general sense of such repositories as material for an activist citizenry:

I found in the archive a capacity to respond to a new generation’s call for social change. I felt the ways it urges a re-calibration of our own artistic tools. I discovered that it is possible to approach archives and collections with our own questions, using them to think through, pierce through, carve through, drill through given concepts and stimulate the imagining of forms of life that fall outside our own habitus.

Zdjelar gets specific. There are “received narratives around Kollwitz’s work” which it is necessary to “abandon”, in order to “foster” the “affective and political force of its sensual and material properties… to see how these forces gain urgency for those of us working with the same motifs (friends, lovers, mothers, children, activists).”

So I am back at the National Gallery. The “received narrative” is seeing Liebsgruppe in the history of modernism, here arranged by European capital city, with Kollwitz shown in the gallery for Berlin, although the catalog also emphasizes her student time in Paris.

What is instead of this? I focus on the feet of both the seated man and the woman in his lap. These are the clearest and most distinctly carved part of both bodies, extending limits of the bronze form beyond its hulk in several directions. The feet propose walking, standing, advancing, as both a physical act and a social, psychological, political “movement” (again in its various senses). This optimism is negated by the static bodies, in which one of the woman’s feet has lost its definition, and any expressive body is absorbed into the molten mass.

I feel solidarity is not solely about mothers, children, lovers, but being suspended between suffering and protest, living and dead, bronze and mud, formal statuary and animal organs. This is as far as I can get.

Short Pieces That Move!, the imprint which publishes Zdjelar’s pamphlet, is a Rotterdam-based project that began as a reading and writing group within the Masters Fine Art course at the Piet Zwart Institute, moving out of the institution and online during the pandemic. As its “About” statement clarifies: “Our interest is in how an existing piece of writing moves, its directions and turns, and how these moves can be modified or repurposed to initiate new movements in readers and the world”.

As a publisher its attractive A5 stapled pamphlets “are low-cost, anti-gatekeeping and anti-prestige”. The first four booklets showcase a variety of positions from which a pamphlet of text could emerge as part of a writing, performing and /or visual art practice. Zdjelar’s more essayistic mode contrasts with Annabelle Binnerts’ Guest which, like her gallery and installation pieces, explores a boundary between isolated typographical arrangements of large font size words and statements, with a capacity for a somewhat surprising feeling, story, and relationship.

Like Zdjelar, Binnert and the other authors write in English, but from an activist, European perspective. So Niels Bekkema’s Bowl, Kom/Glow, Gloed/ Vase, Vaas offers a facing English / Dutch edition of three prose poems, but as the own author’s own creative, ongoing exploration in and between languages, not as an out-sourced, final and likely only translation. In writing is drawing is writing by Vasiliki Sifostratoudaki, an unscrolling text dances a freedom of self, involving a choreography of thought, landscape, and bodily sensation, mostly in English because “greek is too condensed too close to my birthmarks”. But surfacing into the text is Karamanlidika. As Sifostratoudaki writes: “a dialect of the Turkish language written in the Greek alphabet, used by Karamanlides people of 19th century Anatolia”. All these elements evidence a “becoming” of “she I we” that is “constantly in translation/ allowing movement/ to cause exhaustions…” whilst determined to find a way of life that respects how “rest is my right.”

With most presses, the publisher’s stated intent and other books on its list would not necessarily connect intimately to Zdjelar’s Borderwork. Here both appear like another consequence to freeing that “affective and political force” of Kollwitz’s images (as Zdjelar’s films of hands and arms could seem an elaboration on how Binnert’s phrases and words work amidst architecture).

Zdjelar ends the text with a final hymn to the “Leaking. Flowing. Sharing.” by which “Archived bodies speak to living bodies,” a sign-off reminder that when “generations, contexts, practices, materials, bodies touch” then the result is a “border-work.” Over the page there is a small reproduction of the Kollwitz woodcut.

Affectively, Zdjelar’s pamphlet concludes in the darkness that surrounds the printed figures of Mary and Elizabeth. Like putting them in a cave, under a bell or in a hole, Zdjelar told us four pages before, citing African-American poet and critic Audre Lorde’s idea of zones of “darkness” inside the body that are a source of strength and power. This space of Lorde’s is “neither white nor surface; it is dark, it is ancient, it is deep.”

For Mary and Elizabeth, their dark bell surround “holds them. It is in them and all around them.” The black ink letters of this pamphlet now feel closer to the woodcut’s stark economy than I have previously allowed. Like a skilled carver working the wood and aware of the role played by a whiteness of paper, Zdjelar’s essaying mode utilizes its white surround via isolated sentences, paragraph fragments, to keep this Rotterdam-based English tentative, propositional, aware of its doubt, its imposition, any role to explain. It stutters a bodies improvisation from the gasp at a Kollwitz woodcut.

About David Berridge

David Berridge lives in Hastings, East Sussex. He compiles Hugo Pictor's Good Eye, a weekly substack on art books, and writes essays and fiction for The Fortnightly Review, The Montréal Review, and soanyway. His novella The Drawer and a Pile of Bricks is published by Ma Bibliothèque.