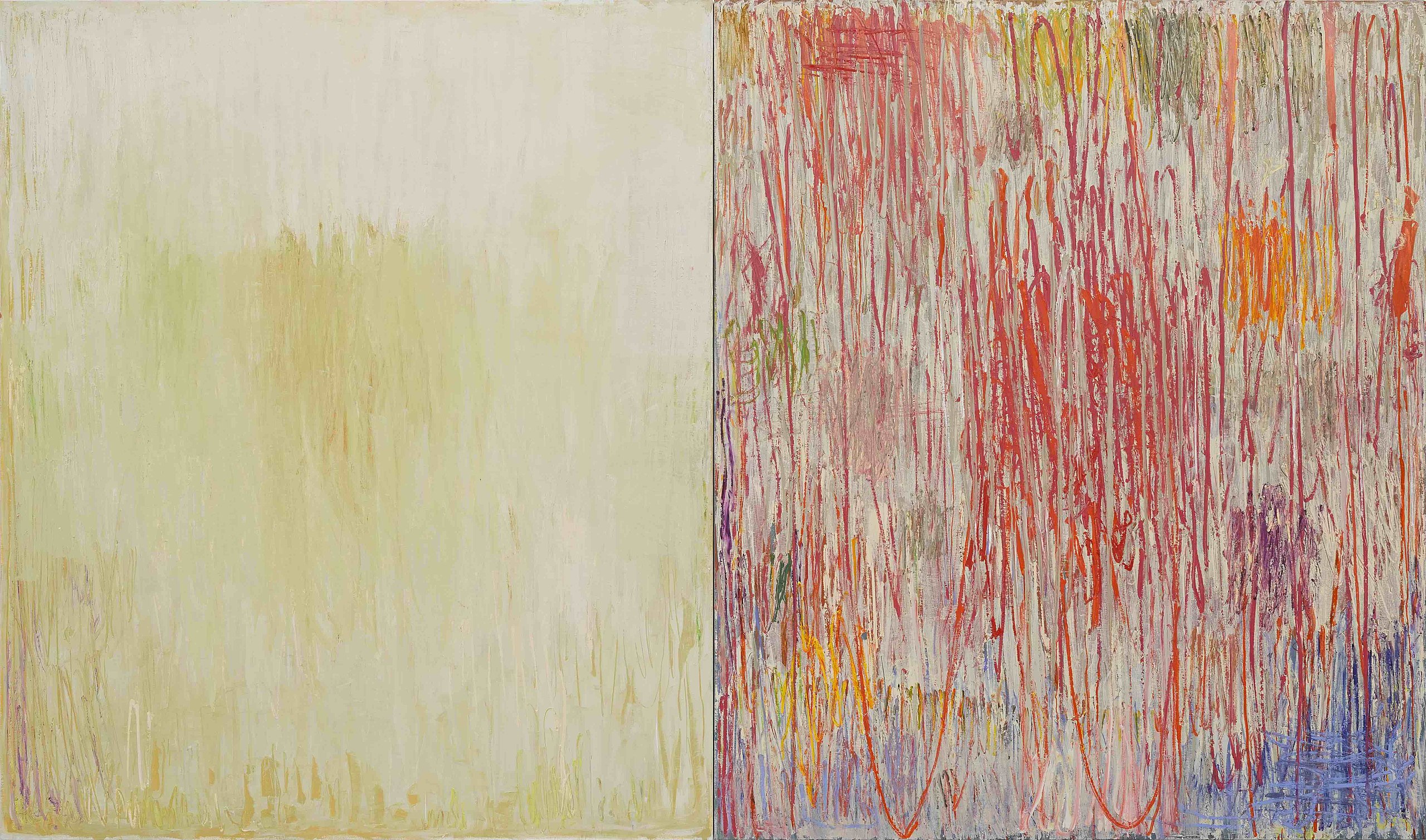

No Room at the End (diptych): Henri Cole

A thirty-foot spider made of stainless steel perches outside of London’s Tate Modern Museum. Artist Louise Bourgeois’ sculpture Maman is grotesque and elegant, vulnerable and out of place on its long uneven legs. Despite its solid construction, the lithe, angular design of the spider makes it seem precarious—more sinew than steel—and the title Maman, French for mother, reinforces this sense of vulnerability; as terrifying as the giant spider may be, she is simply the model of a mother protecting her sac of marble eggs, hovering above horrified museum-goers.

Henri Cole’s poems in Pierce the Skin, the new selected volume published by Farrar Straus Giroux that spans six books and twenty-five years, achieve the same effect of fluidity, transience, and emblematic vulnerability as Bourgeois’ steel spider. Cole’s work, like that of Bourgeois, strives for balance between highly controlled technique with solid materials, and intense emotion as it is revealed in abstraction and symbol. It is no surprise, then, that Cole is drawn not only to Bourgeois’ sculptures but to other visual artists whose work is highly crafted, symbolically charged, and emotionally intense. In a conversation with the journalist Christopher Lydon last year, Cole explained:

I am probably most nurtured by visual art. I love Joan Mitchell, Louise Bourgeois, Vija Celmins, Alice Neel… Visual artists tend to be freer than writers are. Writers seem to have more boundaries—maybe it’s because making art is more physical, but they just seem freer. Also in relation to public events, speaking to the moment in history.

This visual intensity is something for which Cole has striven in his own poems. There is also a clear shift in Cole’s writing from realistic figurative work in the 1980s to more abstract expressionistic work (comparable perhaps to the paintings of Joan Mitchell) later in his career. The beauty of Pierce the Skin is the way in which the poems are presented chronologically, allowing readers to follow the poet’s development from his first book as a young poet, The Marble Queen(1986), through the recent Blackbird and Wolf (2007). While Cole focuses on the same thematic concerns—the creation of self, the family, a Whitmanesque view of nature-as-god, and his own sexuality—throughout all six books, his style shifts subtly from poised almost-photographic tableaux to more fluidly abstract and expressionistic poetry.

The titular poem from the poet’s first collection, “The Marble Queen,” is a portrait of the poet’s mother: a young woman watching a military parade with her little son. The reader is able to visualize the mother clearly, “fixed in her common, girlish pose, her slim legs tucked beneath her,” with fingers that catch in her hair and then “snap free into the air.” The young soldiers, too, are treated with similarly exacting description, their “boyish hair cropped beneath berets.” The scene emerges as from a snapshot: clearly defined, recorded and captured as in a historical document. But the poet does not in this case confine his vision to the closely observed, realistically depicted scene, all exteriority and object; it drifts into the unseen thoughts of the child, the mother who finds that “some unforgettable picture wells inside her” (one that we, as readers, are not privy to, despite the fact that we can see the snapshot from the outside), and the young soldiers parading.

This portrait of the poet’s mother is followed immediately by a second family tableau, “Father’s Jewelry Box.” It is another photo-realist account, this time of the young boy sneaking in his mother’s room while she is away and finding a box with “one copper ‘BVM,’ the Mother of Jesus / faint behind a veil of oxidation, / cozily fastened to Daddy’s war-proof / dog tags worn like a patriarchal / cross across five continents.” The list of treasures reads like the personal effects of a will: five baby teeth, one crystal earring, studs and links, a Masonic medallion. Again, it is as if the reader is looking at an unfaded photograph: each detail is perfectly realized, each item recorded in history. However, in this case, the poem does not enter the father’s mind, or the mother’s as she returns from her hairdresser’s appointment, or even the son’s as he is caught pawing through the treasure box that represents his own family history and the dissolution of his parents’ marriage.

This figurative realism is the dominant mode of the selections from Cole’s first four collections. The artist remains a faithful recorder of the physical world around him, just as the children in “The Zoo Wheel of Knowledge”—the extraordinary titular poem of Cole’s second volume—snap photographs of animals at the zoo. The moment is preserved permanently: the ape’s “lips are cracked and bleeding” and the polar bears swim in their tank. Cole makes the reader a part of this moment; faces are reflected in that of the ape, in the children taking photographs, and in the poet writing everything down.

Although the reader has already been allowed some insight into the mind of the poet-speaker and his relationship to his parents in his very first book, he title of Cole’s third volume, The Look of Things, makes Cole’s documentary style even more explicit. How do things look to the artist? Can “things” be captured in a photographic image; in a poem? In this third book, Cole continues his work as diligent portraitist, and it is in The Look of Things that we see for the first time a deliberate probing of the self, a consideration of where the physical body ends and where the interior self begins, as well as the way these two entities interpenetrate.

The poem “Apollo” returns to the subject of the family, and is an early self-portrait (Cole will make many subsequent self-portraits) in which Cole seeks a sense of the self while retaining his now-typical figurative realism in the poem’s depiction of the external, physical world: it is a snapshot of a young gay man standing beneath a pier discovering his sexuality for perhaps the first time, until the lens shifts from outward to inward, from the physical body to an abstraction of self:

The human self is undeconstructable

montage, is poverty, learning, & war,

is DNA, words, is acts in a bucket,

is agony and love on a wheel that sparkles,is a mother and father creating

and destroying, is mutable

and one with God, is man and wife speaking,

is innocence betrayed by justice,is not sentimental but sentimentalized,

is a body contained by something bodiless.

Shifting the perspective once again, the speaker is back on the beach gazing at a seal that “muscled through the surf, / like a fetus, and squatted on a sewage pipe.” The young man admires the seal for the fact that its “body and self were one,” much as in other poems he relishes the sensual pleasure of riding a horse or gazing into a deer’s black eyes—moments in which the human and the non-human animal transcend the differences of species, language, and experience, and instead relate on a purer level of physicality and emotion.

Similarly, the image of an ape from “The Zoo Wheel of Knowledge” returns in a poem fromMiddle Earth: “Ape House, Berlin Zoo.” The speaker, watching through the bars, is watched in turn: “gazing at me longer than any human has in a long time, / you are my closest relative in thousands of miles.” The connection is mutual, and the speaker realizes that he “cannot tell which of us absorbs the other more.” In this poem and others of Middle Earth, unlike those in his earlier books, Cole moves away from the external world—from photo-realistic rendering—to introspection and internalization. We do not have a crisp visual image of the ape in “Ape House, Berlin Zoo.” We only have the questioning mind:

It is understood that part of me lives in you,

or is it the reverse, as it was with my father,

before all of him went into a pint of ash?

. . .

How can it be that we were not once a family

and now we’ve come apart? How can it be that it was Adam

who brought death into the world?

Increasingly in Middle Earth, and more so in his recent Blackbird and Wolf, the poet turns his focus inward. Like the “novelists of the interior life” he admired as an undergraduate at the College of William and Mary—Henry James, Joseph Conrad, and Virginia Woolf—Cole shifts his emphasis to the life of the mind and the constant interplay of thought and emotion, the shifting drama itself playing out within his own head. In the poem “Twilight,” for instance, he writes:

The mind is the most interesting thing to me;

Like the sudden death of the sun,

it seems implausible that darkness will swallow it

or that anything is lost forever there,

like a black bear in a fruit tree,

gulping up sour apples

with dry sucking sounds[.]

It is evident that in Middle Earth and Blackbird and Wolf, more successfully than anywhere else, Cole becomes a portraitist of his own mutable mind, grasping at the transient and ever-changing self. In “Self-portrait in a Gold Kimono”—a fluid, open-field poem—Cole realizes,

The essence of self emerges

shuttling between parents.

The “I” of the poem is still, as in the early collections, a product of his parentage, formed by his parents yet emphatically not his parents. He realizes, as he will recall in the next piece “Icarus Breathing,” that “a man is nothing if he is not changing.”

Cole’s later poems largely attempt to record these shifting sands of thought and emotion, all the flux and change experienced by the individual mind. It is perhaps for this reason that he has written so many self-portraits in so many guises: “Self portrait in a Gold Kimono,” “Myself with Cats,” and “Self-portrait as the Red Princess,” from Middle Earth, as well as “Self-portrait with Hornets,” and “Self-portrait with Red Eyes” from Blackbird and Wolf. Each self-portrait is expressionistic, internalized, shifting and revealing in its own way. Unlike the static earlier portraits of mother and son, these self-portraits dare to examine the strangeness, contradictions, and fluctuations of self. In “Self-portrait as the Red Princess,” for instance, the speaker is clad in kimono and painted face, dancing on stage; he is a man in drag who can still claim:

I am, after all, a woman,

And not a man playing a woman.. . .

“The flower of verisimilitude,” they call me—[.]

For this moment, at least, the speaker is the Red Princess, the flower of verisimilitude. At another moment, he may be the napping man in “Self-portrait with Hornets” who acknowledges “the self receding from the center of the picture.” Each probing self-portrait grasps at, and ultimately is unable to keep, a defined and limited sense of self because a coherent, unchanging self is in itself a fiction. Like so visual artists, Cole finds his self-portraits subtly or not-so-subtly changing in time. And like Picasso in particular, Cole depicts himself in various guises, revealing components of his inner, emotional-intellectual self.

What does this continued act of self-portraiture achieve? For one thing, in painting himself over and over again, Cole finds that language fails him. He longs for the preverbal, that direct expression he finds so engaging in the visual artist. In Middle Earth’s “Kayaks,” for example, the I-voice reveals,

Everything I feel I am feels distant or blank

as the opulent rays pass through me,

distant as action is from thought,

or language is from all things desirable

in the word[.]

And in Blackbird and Wolf’s “Gravity and Center” the speaker finds that “words, like moist fingers, / appear before me full of promise but then run away / to a narrow black room that is always dark, / where they are silent.” It is the crux of Pierce the Skin and emblematic of Cole’s concern with self and his own “inner and outer worlds:”

“Gravity and Center”

I’m sorry I cannot say I love you when you say

you love me. The words, like moist fingers,

appear before me full of promise but then run away

to a narrow black room that is always dark,

where they are silent, elegant, like antique gold,

devouring the thing I feel. I want the force

of attraction to crush the force of repulsion

and my inner and outer worlds to pierce

one another, like a horse whipped by a man.

I don’t want words to sever me from reality.

I don’t want to need them. I want nothing

to reveal feeling but feeling—as in freedom,

or the knowledge of peace in a realm beyond,

or the sound of water poured in a bowl.

Ending this edition with the fluidity of water is apt. Cole has moved from the precisely verbal, static, photographic realism of his earlier work to the mutable realm of thought, emotion, and sense. One thinks of Keats’ epitaph, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.” Each poem is emotionally intense, like the work of James Merrill or Hart Crane, though Cole’s intensity is unchanging; what does change, however, is the shift from realism and expressionism.

It is in the later poems that Cole takes the greater risks as a poet; poems which are also his most successful. They attempt to capture fully internal thought, almost pre-cognition – ideas and feelings that exist in the individual before language enters the picture. These poems are dynamic rather than photo-static, and they are ultimately more revealing – and more moving – than his earlier poems. No matter how precisely Cole’s early books paint childhood vignettes of the boy and his mother watching soldiers, or the boy snooping through his father’s jewelry, these works do not grapple with emotion and intellect as successfully as the more daring self-portraits in Middle Earthand Blackbird and Wolf.

Taken as a whole, Pierce the Skin demonstrates Cole’s gradual and fascinating development as an artist. The young poet of the 1980s — learning and practicing his technique with a nervous vigilance — is not the same poet of the 2000s, who paints with more confidence and dares to close his eyes to the external world in order to depict more successfully an internal one. His move away from realism is liberating, and the reader gains enormously from this shift. One is no longer revisiting and rehashing old ideas about family and nature by the end — familiar territory — but is instead invited into the vagaries, uncertainties, and mutability of the self. The realist, competent as he was, has become a more successful and daring abstract expressionist.

About Daniel Pritchard

Daniel E. Pritchard is the founding editor of The Critical Flame.